There are articles about the installation of BDA’s that fill my heart with dread: clearly when real beavers stroll into the project they will be trapped outright because they’re destroying their trees or ruining their hydrological experiment. But every now and then one comes along and makes my heart sing…

Returning to past practices for future water management

In 2014, John Coffman arrived in Wyoming as The Nature Conservancy’s new steward for the Red Canyon Ranch and quickly encountered an unforgettable lesson. “We were trying to figure ourselves out on some new country and trying to make sure we were on top of getting the hay meadows irrigated. An intern was having trouble with a beaver plugging a headgate,” he says, preventing water from getting to the fields. They opted to get rid of the pesky beaver, as agricultural operations have done for a long time.

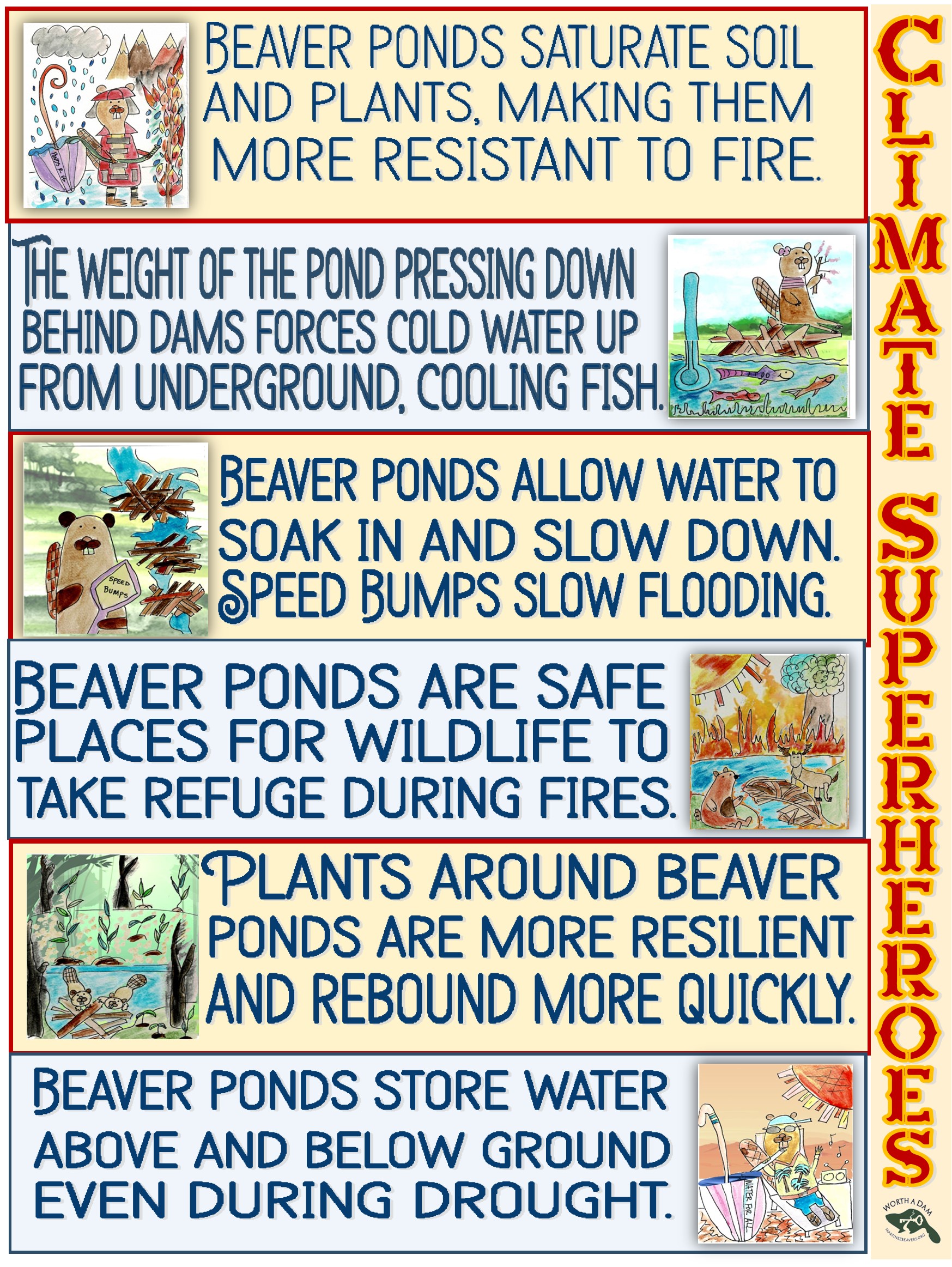

The following year, high spring flows washed away bridges and crossings from the fields, forcing Coffman and his team to restore irrigation ditches and pipes, a resource-intensive process. In a different part of the ranch, however, a stream system that still had beavers showed more resilience to the spring flows. “Instead of those streams eroding away, the [beaver] ponds slowed everything down,” says Coffman. “The ponds filled with sediment and are now growing willows and lush grasses.”

Seven years later, during a mid-July visit, Coffman showed me this historic beaver complex, still thriving after those floods. For twenty feet on either side of the stream, floodplains were green with grasses, willows, goldfinches, and a rattlesnake we were lucky to hear first. Coffman chuckled; he had cautioned me earlier that they’re after the rodents abundant in the area. Four beaver dams bridged deep, still ponds. The beavers built with no regard for clean, neat lines or straight waterways—challenging my understanding of what streams should look like.

After the consequential floods in the spring of 2015, Coffman says, “We came to the observation that there were some serious benefits to having beaver dams and beavers in place.” This beaver complex serves as a model for the conditions that he hopes to restore several streams to. Across an increasingly parched and degraded West, land managers and researchers seeking effective and efficient water management solutions may benefit from the same realization. Perhaps, it’s time to end recent antagonism against beavers and instead form an alliance with nature’s most effective, once prolific waterway engineers.

Wha-a-a-a-t? You mean maybe the beavers had the right idea all along? And maybe when you work for the freakin’ Nature Conservancy you should know better than to kill them anyway? Isn’t that funny? It’s almost like beavers know more about how a stream should work than YOU do!

“None of us in our lifetimes have seen how common beavers would have been,” says Niall Clancy, a PhD student at the University of Wyoming surveying fish diversity in beaver ponds. Before the arrival of Western settlers in the early 1800s, there were as many as four hundred million beavers in America, creating wetland mosaics that covered almost three hundred thousand square miles of land in serene greens and glittering blues. Beavers dam up slower streams to form deep moats around their homes, creating refuges not only for themselves, but also for plants and animals that rely on, and co-evolved with, these dam structures. Series of dams spawn floodplains, wetlands, and ponds—so called “beaver complexes.” Sheltered pools of standing water provide safety for young fish, invertebrates, and amphibians. They are also havens for threatened or rare birds, like sandhill cranes. “The more complex the types of habitats you have, the more types of wildlife you can support,” Clancy says. “Messiness is good in ecology.”

“None of us in our lifetimes have seen how common beavers would have been,” says Niall Clancy, a PhD student at the University of Wyoming surveying fish diversity in beaver ponds. Before the arrival of Western settlers in the early 1800s, there were as many as four hundred million beavers in America, creating wetland mosaics that covered almost three hundred thousand square miles of land in serene greens and glittering blues. Beavers dam up slower streams to form deep moats around their homes, creating refuges not only for themselves, but also for plants and animals that rely on, and co-evolved with, these dam structures. Series of dams spawn floodplains, wetlands, and ponds—so called “beaver complexes.” Sheltered pools of standing water provide safety for young fish, invertebrates, and amphibians. They are also havens for threatened or rare birds, like sandhill cranes. “The more complex the types of habitats you have, the more types of wildlife you can support,” Clancy says. “Messiness is good in ecology.”

Messy can also be how land looks when humans are stewards. “When we think of the past, we need to add Indigenous people,” says Rosalyn LaPier, faculty in the history department at the University of Illinois and enrolled member of the Blackfeet tribe of Montana and Métis. “When the first settlers arrive in the West, what they are seeing are these ecosystems that have co-evolved with plants, animals, and humans.” To survive in water-limited environments, Indigenous communities living between the plains and Rocky Mountains studied and manipulated natural processes. LaPier says that they managed beaver populations to manage water; beaver ponds provided a water source for Native peoples as well as the animals they hunted. Beavers were so important that the Blackfeet considered them sacred and divine. Thus, humans developed a close, symbiotic existence with beavers and their natural worlds.

Isn’t funny how the white man moved in and displaced all the “primative” natives and built their farms and factories and ultimately their universities so that their masters candidates can suddenly report that science shows that maybe those backwards peoples weren’t so backwards after all?

It’s almost like people who lived in harmony with the land for thousands of years knew something we didn’t.

In their places are thousands of miles of down-cut streams like the ones that caused Coffman and his team so much trouble a few years back. In straight, unobstructed waterways, controlling transportation to agricultural fields is the main objective. The force of water travelling quickly does not allow water to collect in the soil or for nutritious sediment to be deposited, so incised banks become unable to support plant life. Without roots to hold the banks together, exposed soil dries and crumbles in the heat of summer, eroding the streambanks.

In their places are thousands of miles of down-cut streams like the ones that caused Coffman and his team so much trouble a few years back. In straight, unobstructed waterways, controlling transportation to agricultural fields is the main objective. The force of water travelling quickly does not allow water to collect in the soil or for nutritious sediment to be deposited, so incised banks become unable to support plant life. Without roots to hold the banks together, exposed soil dries and crumbles in the heat of summer, eroding the streambanks.

Braided stream systems shrink to a single water channel, drying the surrounding land. This cycle eats away at floodplains and wetlands, which otherwise accumulate nutritious sediment, retain water underground (resisting evaporation), and promote biodiversity. With nature’s “sponges” gone, water and nutrients wash out to the ocean, leaving behind arid land and lost habitat.

Reconnecting waterways, reducing erosion, and replenishing groundwater is difficult and expensive. When I asked Coffman about solutions for managing and retaining water on Red Canyon Ranch, he emphasized the hefty costs of bringing heavy machinery and hiring engineers and landscape architects. Such disruption could also set back ecological processes, displacing invertebrates, mammals, and birds alike. The integrity of the ecosystem could take years to recover. Not to mention the challenge of maintaining such an elaborate construction when faced with the unpredictable nature of rivers and streams, which change their courses over time. All in the hope of mimicking the effortless effects of floodplains and wetlands.

Nationally, hundreds of millions of dollars have been allocated toward the labor and materials required to develop water resiliency projects in the West alone. These interagency developments prioritize the storage and protection of water in reservoirs and groundwater, as well as the restoration of wetlands and waterways. Though this large sum recognizes the importance of restoring ecosystems, humans cannot accurately replicate natural processes.

“What [modern] restoration practice has done is borrow from empirical observations and produce average conditions. We are crap at designing for variability and complexity,” explains Joe Wheaton, an ex-civil engineer studying nature’s engineers at Utah State University. Nature, he says, does not adhere to averages but is rather unpredictable. The movement of water and how streams change course are challenges that researchers and engineers cannot account for. Unlike scientists, though, beavers instinctually adapt to and engage with the changing courses of water. They foster jigsaw ecosystems, supporting critters that are co-dependent on one another in ways that scientists often overlook and would be hard-pressed to reproduce. That makes beavers cost-effective tools for maintaining and helping manage the natural water systems that so many people, industries, plants, and animals rely on. For Wheaton, beavers are tools of restoration that engage natural processes, balancing the “mismatch between effort and scope of problem.”

In the most degraded waterways, beavers and their accompanying biodiversity will not return on their own, but we know how to entice them. Clancy’s team facilitates the return of beavers by installing beaver dam analogs, commonly called BDAs). He and his collaborators strategically select for where a beaver’s work is required, targeting heavily eroded streams devoid of life and too deep for cattle to cross. Spanning the width of these channels, they weave sticks and logs, and pack mud to mimic dams. These barriers slow the force of water as it moves downstream while creating pools, the goal being to create a habitat appealing to beavers. Should beavers move in, they build upon and maintain these structures without need for human labor and constant surveillance.

And planting willow right? Lots and lots of willow.

In places where beavers have been reintroduced, ranchers and researchers alike have seen streams flowing anywhere from an extra week to an extra month. Beaver restoration can also replenish groundwater, often a key source for municipal water use. Meanwhile, burying plant materials during the damming process sequesters carbon, preventing it from entering the atmosphere as a greenhouse gas. And in some once-degraded sites where beavers have been successfully introduced, their restoration effectively increased the variety of habitats and the abundance of critters they could support.

Exploring a symbiotic relationship with beavers is still a new but growing practice that has not been without challenges. Coffman says, “Since that situation years ago, we got beavers back creating messes: damming up ditches, plugging up headgates. But we’re trying to approach it a lot differently now.” Rather than treating beavers like nuisances, his management approach centers around the balanced relationship between beavers and stewards. Like Clancy, he is installing beaver dam analogs throughout streams on the ranch—a project that started with five and expanded to over forty structures. Though there are headgates and irrigation ditches where damming is undesirable, Coffman still allows beavers to exist under his watchful eye. After all, early dams can be dug out and individuals relocated—but beavers’ effectiveness in retaining water and restoring floodplains cannot be replicated.

Beavers may not be the ultimate clean-cut solution for our water resource problems. Messy, multi-faceted tools, they challenge the modern concept of controlling water. But researchers and land managers alike have found that nurturing an alliance with beavers, adapting to their activities, and integrating science with natural processes—the way Indigenous peoples have—can help build resiliency in the face of dynamic environmental challenges.

My my my. Beavers are messy little balls of magic. They do grand things in a very cluttered way. This isn’t your father’s concrete channel or shooting stream anymore. It’s a braided wandering tangle of obstructions and sinks. And it’s much much better than you or your engineers could create.

Let it Beaver.

The reason they’re doing this is that the ecological benefits of beaver dams have been lost. Going back to the 1800s. Trappers have reduced the number of beavers there. And because the snowmelt is rarer with climate change, with warmer temperatures, with a recent drought, and without beaver dams, it’s actually changed the environment, and made areas less marshy because water runs through more quickly. And there have been several beaver dams constructed by humans to replicate the environmental benefits of dams built by actual beavers. And there’s actually a hope that the existence of beaver dams built by people will help draw back actual beavers.

The reason they’re doing this is that the ecological benefits of beaver dams have been lost. Going back to the 1800s. Trappers have reduced the number of beavers there. And because the snowmelt is rarer with climate change, with warmer temperatures, with a recent drought, and without beaver dams, it’s actually changed the environment, and made areas less marshy because water runs through more quickly. And there have been several beaver dams constructed by humans to replicate the environmental benefits of dams built by actual beavers. And there’s actually a hope that the existence of beaver dams built by people will help draw back actual beavers.