Back in August of 2021 I wrote am ambitious little post called “Incent-a-beaver” saying that beavers were so important to the golden state it behooved the powers that be to pay landowners to keep them on their land. The idea was based on the incentives farmers are given to keep their fields wet during the flyway season.

Back in August of 2021 I wrote am ambitious little post called “Incent-a-beaver” saying that beavers were so important to the golden state it behooved the powers that be to pay landowners to keep them on their land. The idea was based on the incentives farmers are given to keep their fields wet during the flyway season.

Well I thought it made sense anyway and it must have been a little interesting because afterwards I got an email from Dan Ackerstein who worked with the sustainability team at Google and he said they were interested in how Google mapping technology could help beavers and could we talk.

I was about as excited as I could possibly have been to think that a big power like google could turn their skills to beavers but I was sworn to secrecy and could say nothing. (Which I’m sure as you can imagine was hard for me.) In the end I gave hm some other names and a photo of a beaver that had been taken on the Google Campus a few years back but helping eavers wasn’t the direction they wanted to go in. I thought that was it, an interesting blip on the radar and nothing else.

Until I saw this:

For the first time in four centuries, it’s good to be a beaver. Long persecuted for their pelts and reviled as pests, the dam-building rodents are today hailed by scientists as ecological saviors. Their ponds and wetlands store water in the face of drought, filter out pollutants, furnish habitat for endangered species, and fight wildfires. In California, Castor canadensis is so prized that the state recently committed millions to its restoration.

While beavers’ benefits are indisputable, however, our knowledge remains riddled with gaps. We don’t know how many are out there, or which direction their populations are trending, or which watersheds most desperately need a beaver infusion. Few states have systematically surveyed them; moreover, many beaver ponds are tucked into remote streams far from human settlements, where they’re near-impossible to count. “There’s so much we don’t understand about beavers, in part because we don’t have a baseline of where they are,” says Emily Fairfax, a beaver researcher at the University of Minnesota.

While beavers’ benefits are indisputable, however, our knowledge remains riddled with gaps. We don’t know how many are out there, or which direction their populations are trending, or which watersheds most desperately need a beaver infusion. Few states have systematically surveyed them; moreover, many beaver ponds are tucked into remote streams far from human settlements, where they’re near-impossible to count. “There’s so much we don’t understand about beavers, in part because we don’t have a baseline of where they are,” says Emily Fairfax, a beaver researcher at the University of Minnesota.

But that’s starting to change. Over the past several years, a team of beaver scientists and Google engineers have been teaching an algorithm to spot the rodents’ infrastructure on satellite images. Their creation has the potential to transform our understanding of these paddle-tailed engineers—and help climate-stressed states like California aid their comeback. And while the model hasn’t yet gone public, researchers are already salivating over its potential. “All of our efforts in the state should be taking advantage of this powerful mapping tool,” says Kristen Wilson, the lead forest scientist at the conservation organization the Nature Conservancy. “It’s really exciting.”

You got all that? Beavers are so important we need to know where they are and how many there are. And we can make a computer formula that tells us the answer.s, Oh and just for extra credit notice that the author of this article is Ben Goldfarb.

The beaver-mapping model is the brainchild of Eddie Corwin, a former member of Google’s real-estate sustainability group. Around 2018, Corwin began to contemplate how his company might become a better steward of water, particularly the many coastal creeks that run past its Bay Area offices. In the course of his research, Corwin read Water: A Natural History, by an author aptly named Alice Outwater. One chapter dealt with beavers, whose bountiful wetlands, Outwater wrote, “can hold millions of gallons of water” and “reduce flooding and erosion downstream.” Corwin, captivated, devoured other beaver books and articles, and soon started proselytizing to his friend Dan Ackerstein, a sustainability consultant who works with Google. “We both fell in love with beavers,” Corwin says.

Corwin’s beaver obsession met a receptive corporate culture. Google’s employees are famously encouraged to devote time to passion projects, the policy that produced Gmail; Corwin decided his passion was beavers. But how best to assist the buck-toothed architects? Corwin knew that beaver infrastructure—their sinuous dams, sprawling ponds, and spidery canals—is often so epic it can be seen from space. In 2010, a Canadian researcher discovered the world’s longest beaver dam, a stick-and-mud bulwark that stretches more than a half-mile across an Alberta park, by perusing Google Earth. Corwin and Ackerstein began to wonder whether they could contribute to beaver research by training a machine-learning algorithm to automatically detect beaver dams and ponds on satellite imagery—not one by one, but thousands at a time, across the surface of an entire state.

…So there it is. laid out and clear for us all. The origin story and the key players. So what happened? What is going to happen next?

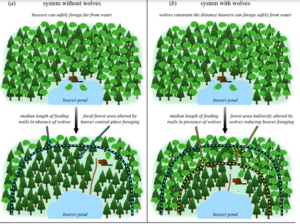

After discussing the concept with Google’s engineers and programmers, Corwin and Ackerstein decided it was technically feasible. They reached out next to Fairfax, who’d gained renown for a landmark 2020 study showing that beaver ponds provide damp, fire-proof refuges in which other species can shelter during wildfires. In some cases, Fairfax found, beaver wetlands even stopped blazes in their tracks. The critters were such talented firefighters that she’d half-jokingly proposed that the US Forest Service change its mammal mascot—farewell, Smoky Bear, and hello, Smoky Beaver.

Fairfax was enthusiastic about the pond-mapping idea. She and her students already used Google Earth to find beaver dams to study within burned areas. But it was a laborious process, one that demanded endless hours of tracing alpine streams across screens in search of the bulbous signature of a beaver pond. An automated beaver-finding tool, she says, could “increase the number of fires I can analyze by an order of magnitude.”

With Fairfax’s blessing, Corwin, Ackerstein, and a team of programmers set about creating their model. The task, they decided, was best suited to a convolutional neural network, a type of algorithm that essentially tries to figure out whether a given chunk of geospatial data includes a particular object—whether a stretch of mountain stream contains a beaver dam, say. Fairfax and some obliging beaverologists from Utah State University submitted thousands of coordinates for confirmed dams, ponds, and canals, which the Googlers matched up with their own high-resolution images to teach the model to recognize the distinctive appearance of beaverworks. The team also fed the algorithm negative data—images of beaverless streams and wetlands—so that it would know what it wasn’t looking for. They dubbed their model the Earth Engine Automated Geospatial Elements Recognition, or EEAGER—yes, as in “eager beaver.”

Wow that’s a lot of work to come around to the acronym EEAGER but okay. I get it. Now for the icing on the cake.

It’s only appropriate, then, that California is where EEAGER is going to get its first major test. The Nature Conservancy and Google plan to run the model across the state sometime in 2024, a comprehensive search for every last beaver dam and pond. That should give the state’s wildlife department a good sense of where its beavers are living, roughly how many it has, and where it could use more. The model will also provide California with solid baseline data against which it can compare future populations, to see whether its new policies are helping beavers recover. “When you have imagery that’s repeated frequently, that gives you the opportunity to understand change through time,” says the Conservancy’s Kristen Wilson.

GOT THAT? California is first and sometime this year we are going to finally know how many beavers the are in the state. And not just be able to infer from depredation permits. This is big news. The biggest.

When beavers count you figure out how to count beavers.