It made me happy to see this headline the other day…I guess Bob isn’t retiring any time soon…

Boucher shares a healthcare plan for the watersheds

At the FLOW Science Symposium, held on September 23, at the River Arts Center in Prairie du Sac, Bob Boucher, founding president of the Superior Bio-Conservancy (SBC) shared his healthcare plan for watersheds, including the Lower Wisconsin State Riverway. His talk was entitled ‘Rewilding with Beavers: Improving Hydrology, Biodiversity and Climate Resilience.’

At the FLOW Science Symposium, held on September 23, at the River Arts Center in Prairie du Sac, Bob Boucher, founding president of the Superior Bio-Conservancy (SBC) shared his healthcare plan for watersheds, including the Lower Wisconsin State Riverway. His talk was entitled ‘Rewilding with Beavers: Improving Hydrology, Biodiversity and Climate Resilience.’

“Beavers are the original ecosystem engineers and habitat builders, and when humans can find ways to work with them and co-exist, the co-benefits will be profound,” Boucher explained. “The hydrological structure of streams with beavers give us the ideal shape to store and retain water on the landscape, increased resilience in the face of weather and climate extremes, improved water quality, stable quantities of water, increased biodiversity, flood reduction and climate resilience.”

And he’s off! One thing that particularly impresses me about Bob is how he gets the media to write down what he says exactly, and not fill in their gaps in attention with their own made up misinformation.

“Beavers were locally extinct in the Milwaukee River watershed by 1730,” Boucher explained. “All rivers in Wisconsin in pre-settlement times had a beaver pond structure.”

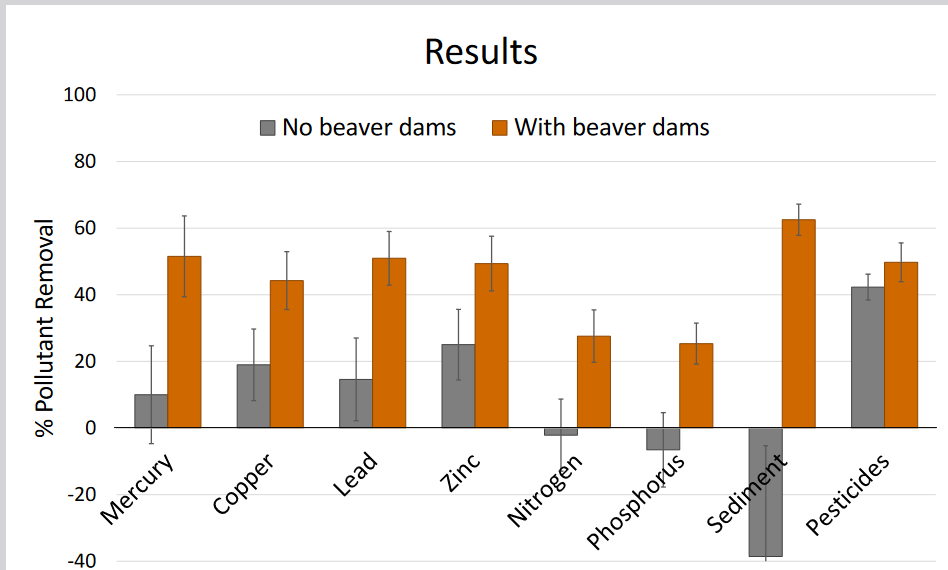

According to Boucher, beavers, when included in a natural watershed and landscape management plan, retain eight times as much volume of water as in watersheds without them. This results in making the watersheds flood resistant. They also filter and cool the groundwater entering the system, producing increased stream health, complexity and biological productivity.

“Essentially, beaver ponds function as sewerage treatment plants and storm detention ponds,” Boucher said. “Beavers create conditions for the abundance of flora and fauna, and natural predators create a counter pressure and help to regulate the populations. Home territories of predators focus on connected routes between beaver wetland complexes.”

Nicely done Bob, tie it into something they can relate to.

According to Boucher, including beavers in a watershed increases the amount of water retained on the landscape. This provides numerous ecological benefits, and supports the goals of ‘biological integrity’ in the Clean Water Act by:

• creating habitat and shelter for fish, plants and organisms

• reduction of pollutants, especially nitrates

• cleaner water through filtration and recharging groundwater

• stabilizes water temperature to be cooler in the summer and warmer in the winter.

“Beaver wetland ponds are keystone habitats to waterfowl, and all bird populations, including ducks, geese, swans, cranes, herons, bitterns, egrets, and more,” Boucher pointed out. “They also create connected habitats that facilitate species migration, which is crucial given the plummet in bird populations in recent years.”

Beaver wetland ponds also, by retaining more water on the landscape, can serve as firebreaks and a refuge for species during a wildfire, according to Boucher.

Perhaps the most significant benefit of co-existing with beavers for humans is the ability of their ponds to support storm water storage. With the increasingly large and intense rainfall events seen in recent years, beaver ponds serve as natural storm water retention structures, similar to the dams built by humans. These structures, like dams, store the runoff and release it slowly.

Dam that reporter is paying attention. Didn’ t I tell you? Bob and I did a talk together for the Oakmont Symposium a couple years ago, a smart ecological group of movers and shakers in Sonoma. He was a man who was often mystified by technology and absolutely brilliant when it came to explaining beavers.

Wisconsin out of step

Boucher pointed out that the State of Wisconsin is completely out of step with most states in terms of beaver management. He said that from 2000-2021, there had been 37,205 beavers killed in the state. He said this had ‘accidentally’ resulted in the killing of more than 2,200 otters.

“Wisconsin DNR sees beavers as threatening trout streams and creating nuisance flooding,” Boucher said. “On June 22, 2023, the Superior Bio-Conservancy filed a lawsuit against the USDA for killing 28,141 beavers, 1,091 river otters and destroying 14,796 beaver dams in 10 years, with all of the activity funded by the Wisconsin DNR. In 2022 alone, these activities hit a record high by killing 3,492 beavers – a figure more then three times the number anticipated in the 2013 environmental assessment.”

According to Boucher, the lawsuit alleges that as a result of this activity, WDNR and USDA Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) have destroyed wetlands, weakened flood resiliency and hampered biodiversity in the State of Wisconsin. The funds used for this ‘Beaver Elimination Program’ total millions of dollars, including revenue from timber sales from Wisconsin’s national forests.

According to WDNR, 32 percent of the state’s listed species are wetland dependent, and the state has already lost 47 percent of its original 10 million acres of wetlands. Thus, Boucher explained, beaver and beaver dam elimination further devastates and destroys the precious remaining damaged wetlands.

“After the 2013 assessment, APHIS failed to carry out the requirement to conduct annual reports on the beaver elimination program until 2020, when the six years prior were reviewed. The conclusion was that a revision to the program was needed because the amount of beavers killed was triple the amount targeted,” Boucher said. “And WNDR is no better, not following any accepted wildlife management guidelines for beaver. There is no WDNR tagging requirement or bag limit for the beaver trapping season, and in 2014, they discontinued all population counts.”

“To avoid being sued, APHIS responded to our lawsuit by August 17,” Boucher said. “We are hopeful that this will cause all stakeholders, and especially WDNR to review and revise the ongoing outdated beaver elimination program.”

Well to be fair, killing lots of beavers is right in step with most states including California. It’s just that the reason they do it is unique in all the world except for the next state over which is also insane. Blowing up beaver dams to save trout is deeply insane. Good luck fixing that Bob.

In summary, Boucher detailed things that citizens can do to produce a beaver management plan in the state that allows us to capture their ecosystem services for the benefit of humans, and allow for co-existence between beavers and humans:

• become a ‘Beaver Believer’ and encourage others to become one too

• talk with elected representatives to promote legislation and policies aimed toward co-existence and beaver protection

• promote non-lethal management

• continue learning, and stay engaged.

Well that’s pretty good advice for everyone and not just the part about beavers! Thanks Bob.

(AP) — For years, beavers have been treated as an annoyance for chewing down trees and shrubs and blocking up streams, leading to flooding in neighborhoods and farms. But the animal is increasingly being seen as nature’s helper in the midst of climate change.

(AP) — For years, beavers have been treated as an annoyance for chewing down trees and shrubs and blocking up streams, leading to flooding in neighborhoods and farms. But the animal is increasingly being seen as nature’s helper in the midst of climate change.