The High Desert Museum in Oregon is one of the most respected museums in the world. It was my father’s favorite and has featured some truly breathtaking beaver exhibits including the interactive grapahic featured in the margin of this page. Once they even asked to use our ecosystem poster in a beaver exhibit.

And now they have this:

Baby beaver from John Day finds home at High Desert Museum

The High Desert Museum recently welcomed a new animal who happens to be an expert engineer, a keystone ecosystem species and the largest rodent in North America.

A baby beaver, called a kit, arrived at the Museum in May. Found in John Day alone in a parking lot, people had searched the area for her family but failed. The kit was then placed into the care of Museum wildlife staff by the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife.

Veterinarians estimated at the time that the animal was only a few weeks old. The beaver was very weak and dehydrated, weighing just 1.4 pounds. Wildlife staff spent the next several months working to formulate an appropriate diet and nurse the kit back to health.

“The Museum’s wildlife team was tireless in researching appropriate diet options and providing around-the-clock care,” says Museum Executive Director Dana Whitelaw, Ph.D. “Their dedication to providing the best care is exceptional.”

It took most of the summer for the beaver’s condition to improve, but the baby slowly began to gain weight and strength.

Six months later, the beaver is healthy and growing, now at almost 17 pounds. Staff have built a behind-the-scenes space to meet a beaver’s needs, complete with a pool for swimming. The kit eats a species-appropriate diet of native riparian browse such as willow, aspen and cottonwood, supplemented with vegetables and formulated zoological diets to ensure proper nutrition.

The plan is that when ready, the beaver will become an ambassador for her species by appearing in talks at the Museum that educate visitors about the High Desert landscape.

Just to be clear I HATE when orphans are raised in captivity to be ambassadors but of all the places to be kept on display this is probably the creme of the crop. And who knows, maybe he’ll get a companion one day.

“The beaver is doing well and learning behaviors that assist with her care,” says Curator of Wildlife Jon Nelson. “She is learning target training, how to sit on a scale to be weighed and to present her feet for voluntary inspections and nail trims. She also enjoys time playing in the Museum’s stream after hours.”

The beaver is believed to be female. It’s challenging to conclusively identify male or female beavers.

The opportunity to name the beaver was auctioned at the 2023 High Desert Rendezvous. The winning bidder has yet to select a name, which must be appropriate for the Museum and connected to the High Desert.

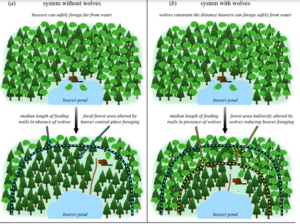

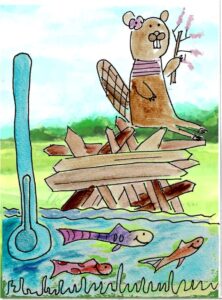

An estimated 60 million to 400 million beavers once lived in North America, creating wetlands and ponds. The dams built by these “ecosystem engineers” slow streamflow, raise the water table and reduce downstream flooding and erosion. Beavers also help birds, fish and other wildlife and native plants to thrive by creating habitat.

Beaver populations dropped dramatically in the last two centuries with demand for beaver pelts for clothing, most notably hats, in the mid-19th century. Their dam-building activities also at times prompt people to consider them a pest on their properties.

Today in the West, restoration of the beaver is underway and humans in some areas are mimicking its dam-building behavior in order to restore healthy High Desert riparian areas.

“The history of beavers in the High Desert is a profound one,” Whitelaw says. “We hope to be able to share the new beaver at the Museum with visitors soon to help tell the meaningful stories about the role these animals have to play in healthy ecosystems.”

The Museum cares for more than 120 animals, from otters to raptors. Many of the animals are nonreleasable, either due to injuries or because they became too familiar with humans. At the Museum, they serve as ambassadors that educate visitors about the conservation of High Desert species and landscapes.

I’m sure she’ll be called rattle snake or Justin soon. But remember, two years ago the museum dd the best exhibit ever for beavers and the difference they make so take heart little one, at least your among friends.