If you traveled north of Montana and kept on snow plowing until you passed Calgary you’d come to the city of Airdrie, And you have dropped into a most unusual presentation to the city council there. Meet champion Barbara Kowalzik who I suspect is going to be our very good friend soon.

Resident lobbies council for better wildlife management practices

With the City of Airdrie putting a pause on trapping and killing beavers of the Waterstone community, an Airdrie resident presented to council asking that the City adopt a policy to co-exist with beaver populations on November 7.

With the City of Airdrie putting a pause on trapping and killing beavers of the Waterstone community, an Airdrie resident presented to council asking that the City adopt a policy to co-exist with beaver populations on November 7. Summerhill resident Barbara Kowalzik, who has lived there for 13 years, made a presentation to council offering some information to consider as the City explores alternative to trapping and killing destructive beaver populations in the community.

While she presented as a concerned resident, Kowalzik holds a bachelor degree of sciences, and has over a decade of experience in wildlife conflict management.

Kowalzik said that the continued destruction of public and private properties has shown that Airdrie’s current management methods have been ineffective.

“The beaver lodge in my community has existed long before I moved here, and over the last 10 years I’ve seen these beavers relocated unsuccessfully and managed a number of times. I feel that I can say with confidence that we have an opportunity here to make a change because what we are doing is not working,” said Kowalzik.

Ohhh hoo hoooo. I am liking Barbara! What a celestial entrance! I wish I had known enough once upon a time to be able to march in and present to the city council that they should do it better.

“Many trees in my community have been wired, but unfortunately most are wired insufficiently or the cages aren’t properly secured which allows beavers access,” she said.

“Many trees in my community have been wired, but unfortunately most are wired insufficiently or the cages aren’t properly secured which allows beavers access,” she said.

“I think the fact that beavers have taken a number of large poplars over the last few months speaks to the fact that there’s room for improvement.”

She added that she believed aggressive behaviours demonstrated by beavers were an overstated concern.

“Although beavers are social animals, they’re not aggressive and attacks and bites are exceptionally rare. I can say this from first-hand experience working with wild beaver populations,” said Kowalzik.

“I’ve heard the beavers in my community be referred to as aggressive a number of times, and implying this aggression as justification for trapping,” she said.

Beavers aren’t aggressive buddy. But watch out because I AM! Just putting chicken wire on a tree isn’t the same thing as protecting it. We know that.

“I would suggest that defensive behaviours, such as posturing and vocalizing, has been mislabelled as aggression, which can be very misleading as it relates to public safety.”

She suggested preventative measures as a solution. Those included a proposal to paint tree bases in sand mixures, and a practice called ‘diversionary planting,’ which equates to placing specific plants near beaver colonies to attract them so they don’t turn to other publicly or privately-owned trees and shrubs.

Another proposal was to explore pond levellers to manage water levels and mitigate beaver activity in certain areas.

Kowalzik’s presentation cited a study conducted by Stella Thompson published in the January 2021 edition of the Mammal Review, which estimated that environmental services provided by beavers can amount to $179,000 USD per square mile annually.

The big guns. Cities waste money by trapping beavers. Everything else falls on deaf ears. Keep going Barbara,

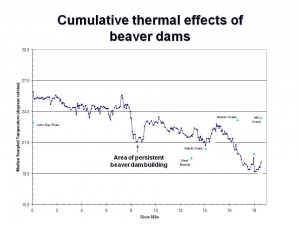

She said that could be taken into consideration when looking at the 2018 Nose Creek Watershed Water Management Plan, which highlighted the unhealthy ecosystem of the watershed.

“It’s polluted with phosphorus, nitrogen, and fecal coliform. Not only do beavers on the landscape help increase water quality, but they also help enhance biodiversity,” she said.

“It has a ripple effect, and I think the riparian habitat in Waterstone is a great example of this. There’s mink, muskrat, neotropical songbirds, numerous invertebrates, and numerous species of wild plants.”

She said the challenges presented could potentially be leveraged into new opportunities for innovation.

“Mutiple beavers in my community have been trapped and killed over the last month, but beavers still remain in the lodge and trees still remain accessible,” said Kowalzik.

Ohh hoo hoo Barbara. You got ’em on the ropes now! Don’t let up. Keep wielding that sword until they say uncle.

“I’m hoping we can leverage some of the resources available to us in order to make some well-informed decisions moving forward.”

Councillor Ron Chapman said he was somewhat divided on the issue because of the costs and liabilities they were presenting within the City.

“In the wild they are great, but the City of Airdrie is not a wild environment for them. In a municipal setting, I don’t see it different than having a mouse in your kitchen,” said Chapman.

Hmm does the mouse save money on your water bill and fight fires? Asking for a friend.

“If you have a mouse in your kitchen, you have to get rid of it because it’s doing damage. It’s going to continue to do damage while it’s there,” he said.

“I’m not convinced that we’re going to be able to… co-exist with them.”

The City of Airdrie is looking to do some additional research with the insight of other wildlife experts on how to best approach the beaver problem.

Councillor Candice Koleson said she looks forward to seeing what comes from those discussions, but added that she recognized that there’s a very apparent problem for the municipality.

“They are incredibly destructive. Big trees have been taken down overnight, and it’s very difficult for us to be able to justify that destruction,” she said.

The week prior to the meeting saw beavers take down a tree along Main Street, which has only raised safety and liability concerns around the critters remaining in an urban environment.

Well yes it’s easier to Kill a problem than to solve it. I agree. But is it better for the community? Is it better for the green spaces in your community? Better for your water quality? Better for the mental health of your residents? I’m going to guess the answer to that is “NO”.

Barbara we need to talk.

Reports of beaver trapping this fall at Saugatuck’s Peterson Preserve are true, said city manager Ryan Heise.

Reports of beaver trapping this fall at Saugatuck’s Peterson Preserve are true, said city manager Ryan Heise.