This is my new favorite article. It is part of the very best chapter in Leila Philip’s new book, I saw it reprinted yesterday but figured we needed to face groundwater before we had treat. It’s Christmas Eve eve. My favorite day of the year. So get ready for your treat.

“Are you ready to open the closet and enter Narnia?”

“Are you ready to open the closet and enter Narnia?”

Scott McGill stands at the edge of Long Green Creek in the Chesapeake watershed. I can hear rustling and chirping, then the loud, regal cry of a hawk.

“I’m ready.”

McGill is the founder of a visionary environmental restoration company called Ecotone, based in Forest Park, Maryland. A slim man dressed in jeans and a green T-shirt, he exudes enthusiasm and confidence. McGill gives a quick nod then disappears into a thicket of willows.

I am only a few steps behind, but the underbrush swallows him so completely that for a moment I can follow only by listening for the sloshing sounds of his boots plunging forward through water. His wife, Moira, relaxed and cheerful, brings up the rear.

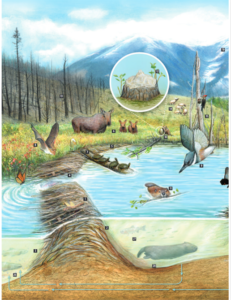

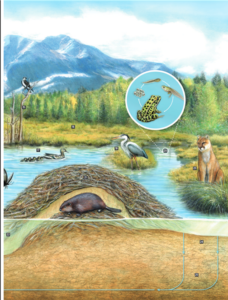

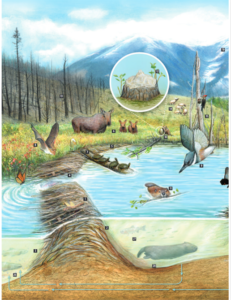

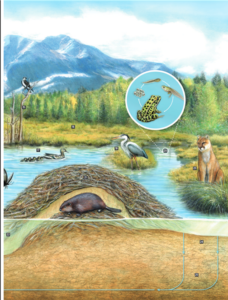

Narnia is what McGill calls the wetland area that beavers have created here by damming the creek that runs through Long Green Farm, fifteen miles north of Baltimore. As soon as I step into the wetland, the landscape changes so dramatically, it feels as if I might just have slipped through the enchanted wardrobe in C. S. Lewis’s famous series. While just a moment ago we were standing on a farm road, flanked on either side by wide fields of soybeans and hay, we are now moving through an iconic forest wetland.

First of all, I love LOVE the photo with this article. I can’t believe we’ve never seen it before. Go back and look more closely. It’s stunning. And second of all even thought it’s delightful to suggest we’re entering Narnia of course it’s not true.

Because in Narnia beavers eat fish.

The air has cooled and before us the ground is silvered with water. Somewhere near the center and down deep in this swampy expanse, Long Green Creek is running through, but you wouldn’t know it unless you hiked to the far end and saw the dam that the beavers have built there. Spires of dead trees punctuate the scene, which is teeming with birds. Meanwhile, everywhere I look I see an extraordinary variety of grasses, sedge, and aquatic vegetation. McGill turns around and grins. I am glad I wore my waders, because the water is way above my knees. Once they entered the wardrobe, that famous portal to Narnia, the kids met Mr. and Mrs. Beaver, who stood on two legs and spoke to the children, becoming their guides. The beavers we are looking for here moved in six years ago. McGill looks admiringly across the water. “When I walk in here it’s another world.”

McGill is proud to be known in the environmental restoration industry as the “beaver whisperer.” He’s evangelical in his belief that beavers can help solve environmental problems. He thinks it is a tragedy that they are part of our history, but not part of our culture. Here in the Chesapeake watershed, in Maryland, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey where he does most of his work, he has been striving since 2016 to help shift the culture around beavers and stream restoration by showcasing what he calls the “ecosystem services” of beavers. Let the rodents do the work is one of his mottos.

He believes it is possible to “reseed” the East Coast landscape with beaver, and he has done enough restoration work with them now to prove that these efforts work and can make a difference, saving his clients, which include individual landowners, farmers, towns, and municipalities, a great deal of money. Environmental restoration is now a multibillion- dollar business throughout the United States, but especially in Maryland where in part due to the incredible rate of development, every county is now under pressure from the Environmental Protection Agency to help clean the water running into the Chesapeake Bay.

I love that this article gives Scott the fame he deserves. I suppose he can be referred to as the Beaver Whisper if he likes but honestly that title has been tossed around more than the title of Marilyn Monroe’s boyfriend. The first time I know of it being used was in Jari Osborne’s original Canadian version of the beaver documentary.

I love that this article gives Scott the fame he deserves. I suppose he can be referred to as the Beaver Whisper if he likes but honestly that title has been tossed around more than the title of Marilyn Monroe’s boyfriend. The first time I know of it being used was in Jari Osborne’s original Canadian version of the beaver documentary.

But who knows, maybe that wasn’t the first either.

I loved this idea that beavers, these wonderfully weird animals that in so many ways had made America a country, could now play a role in helping to save the land itself. All up and down the Atlantic seaboard, if you looked, you could find beavers at work. And when they were left alone for long enough, within decades they could reshape the ways water moved through the land, bringing back the rich biodiversity of paleo- rivers. But those areas were for the most part open land, or tracts of forest set aside for scientific study and conservation. Could beavers be used successfully for large- scale stream restoration and floodwater control in places full of people? McGill had suggested I start my visit here on Long Green Creek because he considers it a “poster child” for how beavers have been put to work.

To tell the truth I don’t really understand the fascination with the word “weird”. Humans have four limbs and yet the walk upright. Dolphins feel like wet rubber and yet they eat fish. Elephant noses are longer than their tails and they have wrinkly skin. We’re all weird, if you get right down to it I’m weird. You’re weird. We are made for particular niche roles that others can’t fill.

And that’s a good thing.

After we have finished our tour of the extensive wetlands the beavers have made and are once again standing on the farm road, McGill points back to where the beavers are living.

“To build a storm water management pond with that kind of water retention would cost one to two million dollars,” he says matter-of-factly. I am visibly stunned at the price. “One to two million?”

“Yes,” answers McGill. “You have to build the embankment, the core, an outlet structure, you have to design and plan the whole thing. We’ve built those; we have contracts with counties throughout Maryland where it is one after the other. But beavers did all this . . .” He swings his arm in a wide gesture for emphasis. Moira, who has been listening, interjects with a grin, “For zero dollars!” She laughs, and so does McGill, both of them energized and delighted by this thought.

“We do stormwater management, construction, renovation, fire retention areas, we do a lot of stream wetland restoration,” he continues, “but the thing is the water quality benefits of a beaver pond are very much similar to what we want to see in an engineered storm management pond.”

Ahh yes, Beavers are the original ‘friends with benefits’. It honestly beats the hell outta me why we keep killing them instead of throwing them birthday parties every time they build a new dam,

Once he is on the subject of the economic savings of utilizing beavers, McGill has no limit of case studies to share. He begins to describe some restoration work Ecotone did on a tidal creek twenty years ago. “The county and state were spending millions dredging it every ten years,” he explains. When the town called up to ask McGill to do something about some beavers that had moved in, McGill convinced them to put in a flow device instead of removing them. The flow device cost about $8,000 to install and monitor, but McGill figures that the ecosystem services that the beavers there provide is probably worth millions.

Once he is on the subject of the economic savings of utilizing beavers, McGill has no limit of case studies to share. He begins to describe some restoration work Ecotone did on a tidal creek twenty years ago. “The county and state were spending millions dredging it every ten years,” he explains. When the town called up to ask McGill to do something about some beavers that had moved in, McGill convinced them to put in a flow device instead of removing them. The flow device cost about $8,000 to install and monitor, but McGill figures that the ecosystem services that the beavers there provide is probably worth millions.

“We try to take the approach where we coexist,” he continues. “We say, ‘Let’s let the beaver stay and get the ecosystem benefits they provide.’ The creation of water storage and sediment storage—the cost-benefit ratio of using beavers is astronomical.”

Yes it is. All the good beavers could do us if we could only LET them. And if we added into that ratio all the wasted money we spend trying to get rid of beavers it would blow your mind clean away.

You can pick up your copy of this fun read

You can pick up your copy of this fun read