Ooh I have been waiting for this, every time I read an article about beavers being worse than wildfire or cause giardia in the arctic I would fantasize about Ben Goldfarb come swooping in with his swashbuckling adjectives to rescue beavers. Well the day has finally come. In Audubon magazine.

Time in the Alaskan Arctic moves slowly. Layers of permafrost inter the chilled remains of mammoths and early humans; dwarf birches and lichens grow at almost imperceptible clips; glaciers creep down mountains at annual rates measured in millimeters. Abrupt disturbance is rare: There are no hurricanes or tornadoes, and few floods and wildfires. Landscapes are static. Change, when it comes, is subtle and incremental. Besides the beavers.

Time in the Alaskan Arctic moves slowly. Layers of permafrost inter the chilled remains of mammoths and early humans; dwarf birches and lichens grow at almost imperceptible clips; glaciers creep down mountains at annual rates measured in millimeters. Abrupt disturbance is rare: There are no hurricanes or tornadoes, and few floods and wildfires. Landscapes are static. Change, when it comes, is subtle and incremental. Besides the beavers.

Climate change has given the industrious mammals a foothold in Arctic Alaska, the vast tundra ecosystem in the northern reaches of the state. As the region has warmed, new willows have sprouted and invited beavers, who both eat the inner bark and harvest stems for dam-building material. Beavers have also benefited from more open water, as their ponds are less likely to freeze solid in balmier winters. Near the city of Kotzebue in western Alaska, beaver dam construction spiked 50-fold between 2002 and 2019. “Just about everywhere you go, you’re going to run into a beaver dam,” says Cyrus Harris, an Iñupiaq hunter and natural-resource advocate in Kotzebue.

Oh at last I feel like I can breathe and stop whacking things away with a racketball racket.

Plenty of animals, including moose and red foxes, are moving into the fast-warming Arctic. But beavers aren’t just taking advantage of environmental change; they’re accelerating it. The indefatigable architects’ dams transform streams into chains of ponds and wetlands so immense they’re visible from space. In its 2021 Arctic Report Card, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration called beavers a “new disturbance” transmogrifying the tundra “stream by stream and floodplain by floodplain.”

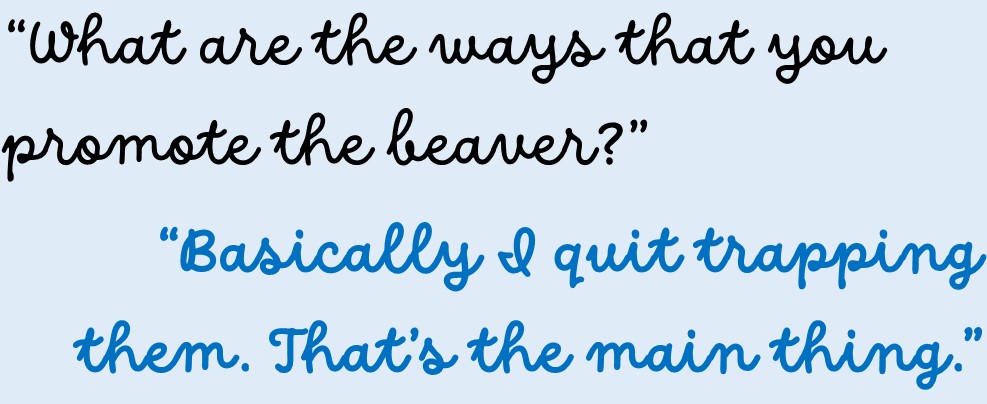

The Arctic isn’t the only place beavers are booming. Once nearly exterminated for their pelts, 10 to 15 million beavers inhabit North America; they thrive in ecosystems as diverse as boreal forests and southwestern deserts. Conservationists and scientists hail them as ecological champions whose ponds filter out heavy metals and other pollutants, slow wildfires, store water, and furnish habitat for birds including Hooded Mergansers and Trumpeter Swans. Today states like California, Colorado, and Washington are aggressively pursuing their restoration. “There’s been this great positive feedback loop of encouragement for working with beavers,” says Emily Fairfax, a University of Minnesota beaver researcher. “They’re a super-valuable ecosystem engineer.”

Whew. The entire article is worth reading twice. Click on the headline to go savor it yourself. I’ll just try to give you some favorite parts.

This was a different beaver story than I was accustomed to telling. In 2018 I published a book on the movement to re-beaver North America, and I’ve seen beavers work wonders: They’ve turned seasonal trickles into perennial streams, revived trout populations, and captured contaminants better than many wastewater treatment plants. They’re the ultimate keystone species, stout miracle workers that can address an array of environmental ills. Ken Tape, a University of Alaska Fairbanks biologist who studies the species, likewise seems more fascinated than perturbed by their Arctic takeover. “It’s becoming a more dynamic place,” he says, “and it’s hard not to be excited about that.”

Oh gosh an actual moment where I don’t feel like stuffing Ken Tape in a pillowcase and tying shut the opening.. That is rare. Ben is a good writer.

One morning I drove with Tape and his research team north from Nome along a potholed dirt highway. Although the town lies just below the Arctic Circle, the treeless, green-gray tundra gave off strong Arctic vibes. Low clouds clung to the mountains and musk ox browsed the roadside, lending the scene a Pleistocene cast. Telephone poles unmoored by thawing permafrost tilted at funhouse angles.

Tape and a colleague set to measuring the depth of the permafrost, the underground layers of soil, sand, and gravel bound together by long-frozen water. They walked roughly 200 feet from the pond and jabbed a long metal pole into the tundra. It sank about a foot, then thunked audibly against a rock-hard lens of permafrost. They moved closer and closer to the pond, shoving the probe into the ground as they went. The nearer they got to the water’s edge, the deeper the probe went. At the pond’s marshy fringe, the 10-foot probe disappeared into the earth without hitting ice at all. To the extent the researchers could measure, the permafrost had vanished.

This wasn’t surprising: As an Arctic adage goes, water is the death of permafrost, just as it’s death to the ice cubes in your glass. And beavers, by spreading water across the landscape and pooling it underground, are permafrost killers. As permafrost thaws, it releases carbon that has been stored for centuries within frozen plants, animals, and other organic matter. That, in turn, is devoured by methane-emitting microbes. In a 2023 study, Tape and others found that beaver ponds on the Arctic tundra cough out around 50 percent more methane, a greenhouse gas roughly 30 times more potent than carbon dioxide, than other waterbodies.

Ok. There it is the bad news. Somehow it is less horrifying when Ben delivers it. Keep reading.

Before we indict a humble rodent for the despoliation of the Arctic, some perspective is in order. While beavers are releasing methane in Alaska, elsewhere they sequester carbon by storing organic material in pond-bottom sediment. And compared to ongoing and proposed development—the Willow oil-drilling project in the National Petroleum Reserve, for example—beavers hardly register as a source of atmospheric carbon or a force of landscape-scale change. If anyone was responsible for damaging Alaska, it seemed to me, it was fossil fuel companies and drill-happy politicians. “It’s almost like they’ve become a scapegoat,” says Seth Kantner, a writer in Kotzebue.

Whatever beavers mean for the carbon cycle, there’s no ambiguity about their biodiversity benefits. In the Lower 48, they furnish breeding pools for frogs, rearing ponds for trout, and fishing grounds for otters. Few animals profit more from beavers than birds. Waders like Great Blue Herons stalk fish in their ponds; cavity nesters like Wood Ducks dwell in drowned trees; and warblers of all stripes perch and feed in coppiced willows. In Poland, researchers have found that overwintering birds are more diverse and abundant not only at beaver ponds themselves, but well into the surrounding forest—making beavers an aquatic rodent with massive terrestrial impact.

The scene suggested an idea that had been gnawing at me for days: Rather than agents of Arctic destruction, beavers may be agents of Arctic adaptation. Researchers estimate that climate change already has nearly half of the world’s species on the move. The Arctic is becoming a refuge for some of these immigrants: Salmon follow receding glaciers into northern rivers; moose browse on emergent willow; migratory birds arrive on their breeding grounds earlier and depart later. Elsewhere on the continent these creatures find succor in beaver ponds; they may in the Arctic, too.

Agents of adaption. Beavers are parachutes for the wildlife that is driven northwards by climate change.

For all of beavers’ virtues, however, few animals are more polarizing. In the Lower 48, they’re blamed for flooding roads, felling fruit trees, and damming irrigation ditches, offenses for which workers for Wildlife Services, the USDA’s branch tasked with managing problematic animals, kill more than 20,000 every year. We embrace beavers one day, execute them the next.

This paragraph made me especially happy

While most people considered it a given that beavers had recently arrived, I couldn’t help but wond0er whether they were truly colonizing the Arctic or recolonizing it after being wiped out by fur trappers decades earlier. It wouldn’t be the first time humans had purged beavers from a landscape and then claimed they’d never been there: The rodents were considered nonnative to much of California until the 2010s, when researchers assembled archaeological and linguistic evidence proving they’d lived in the state before being nearly extirpated in the 1800s. Arctic paleontologists have likewise found scattered beaver bones and teeth dating back 8,000 years, and place names like Beaver Creek, near Nome, hint at their possible presence. On the other hand, the paucity of beaver stories among Indigenous communities argues for their absence. “One of the questions we haven’t really been able to answer is where beavers were before the fur trade,” Tape says.

Oh my goodness. Ben is asking all the right questions.

They’re also conspicuous harbingers of a far more powerful force: climate change. The Arctic has warmed nearly four times faster than the global average since 1979, and for subsistence hunters like Harris, who describes the natural world as his “supermarket,” hotter temperatures have spelled chaos. Sea ice freezes later in fall and thaws earlier in spring, impairing the pursuit of marine mammals; storms batter the coast; novel species replace familiar ones. “We’re seeing lots of changes,” Harris says. “Everything is all together, all at once.” Arctic beavers confer their own distinct impacts, yes, but it occurred to me that they may be resented, in part, because they’re symbols—flesh-and-fur portents of a warming world.

They’re also conspicuous harbingers of a far more powerful force: climate change. The Arctic has warmed nearly four times faster than the global average since 1979, and for subsistence hunters like Harris, who describes the natural world as his “supermarket,” hotter temperatures have spelled chaos. Sea ice freezes later in fall and thaws earlier in spring, impairing the pursuit of marine mammals; storms batter the coast; novel species replace familiar ones. “We’re seeing lots of changes,” Harris says. “Everything is all together, all at once.” Arctic beavers confer their own distinct impacts, yes, but it occurred to me that they may be resented, in part, because they’re symbols—flesh-and-fur portents of a warming world.

During my week in the Arctic, signs of beaver ingenuity were everywhere. Although all beavers are skilled diggers, the submerged networks of tunnels and cavities they’d excavated with their paws here were much deeper than those I’d seen in more temperate climes—likely to prevent ponds from freezing solid during the unforgiving winter. The lodges, too, were gargantuan, up to 10 feet tall and 30 feet wide—swollen with insulating mud. The beavers themselves were unusually active, often emerging to slap their tails in irritation or grab a willow snack. Elsewhere beavers favor a nocturnal lifestyle; here they’d adjusted to a land without night.

Honestly the entire article is perfect]y written. And the photos will blow your mind. I can hardly do it justice.

What’s next for the Arctic’s beavers? Today Alaska’s North Slope, the coastal plain that plunges away from the Brooks Range and toward the Beaufort Sea, remains free of beavers. To reach the slope, the rodents would have to waddle over a mountain pass patrolled by wolves or disperse west along the coast from the Kongakut River—daunting but not impossible tasks. “It kind of looks like it’s a matter of time,” says Tape. Like humans, beavers will soon have few lands left to conquer.

Like us, too, they will continue to transform the places they already live. Flying back to Nome, we soared over myriad sun-flecked lakes and streams, a rolling expanse ribboned with open water and fringed with halos of new willow. Although we passed a few lakeshore lodges, I was struck not by how many beaver ponds we saw, but by how few—and how much prime habitat beckoned to future waves of colonists. The future, it seemed, would be beavery.

I hope everyone’s future is beavery too. Sorry. I just do.

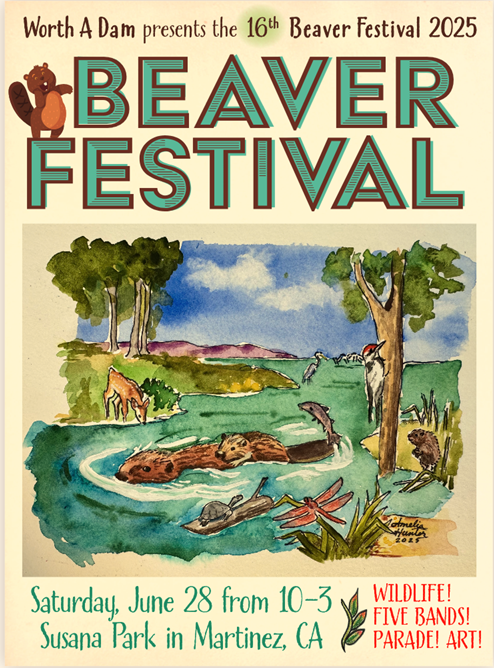

Although it sounded dire for a while when an emergency order about them appeared on the Board of Health’s agenda, it turned out to be a good day in the end for the Turner’s Pond beavers.

Although it sounded dire for a while when an emergency order about them appeared on the Board of Health’s agenda, it turned out to be a good day in the end for the Turner’s Pond beavers. to healthier water. They MAKE it healthier.. They can move into skanky toxic water. Like Chernobyl and Mt St Helens where they were some of the first species back,. And their dams start to clean the water for everyone ELSE. They are do gooders.

to healthier water. They MAKE it healthier.. They can move into skanky toxic water. Like Chernobyl and Mt St Helens where they were some of the first species back,. And their dams start to clean the water for everyone ELSE. They are do gooders.