I think we found a new best beaver friend, in Golden BC,about 4 hours north of Spokane. Her name is Annette Lutterman and she’s a self employed PhD and Ecologist who happens to agree with us.

Beavers: our unsung climate heroes

Every year in the Kootenays we witness more extreme wildfires, floods and drought. It turns out that a brilliant little animal that we nearly hunted to extinction could play an important role in protecting our homes and the environment from these extreme weather events.

That’s right — not only are beavers brilliant ecosystem engineers that create habitat for countless other species, they also play a key role in the fight against climate change.

Well sure. we had a whole festival about that. It’s nice that we think alike.

Beavers’ rich wetlands are like sponges; they store water during drought and make ecosystems less vulnerable to extreme weather changes. They also keep surrounding areas wet throughout so they don’t readily burn, and instead act as firebreaks.

Beavers’ rich wetlands are like sponges; they store water during drought and make ecosystems less vulnerable to extreme weather changes. They also keep surrounding areas wet throughout so they don’t readily burn, and instead act as firebreaks.

Not only do beaver ponds resist wildfire, they also mitigate flooding by controlling and releasing water more gradually. “They slow the water as it comes down the mountainsides,” says ecologist Annette Lutterman, who has spent years researching beavers, particularly around her hometown of Golden.

These dams often work in conjunction with one another. Near Kicking Horse Mountain Resort, one beaver complex has seventeen dams in a row along one stream! Together, they allow raging spring snowmelt to be absorbed into the soil and surroundings rather than causing flooding.

Communities that have suffered extreme flood events over the past few years are concerned about logging in upper parts of the watershed because it also increases flash flooding. Beaver infrastructure helps.

Sponges and superheroes. That’s it exactly. Slow the water down and manage it safely over the long term. That’s their motto.

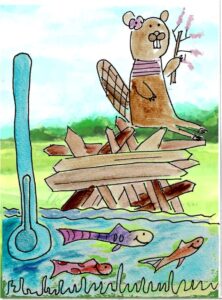

With only their bare paws (and incisors!), beavers shape freshwater habitat — building wetlands and marshes that are incredibly rich in biodiversity. These beaver-built ecosystems create invaluable habitat for other species including fish, mammals, waterfowl, songbirds, amphibians and insects.

With only their bare paws (and incisors!), beavers shape freshwater habitat — building wetlands and marshes that are incredibly rich in biodiversity. These beaver-built ecosystems create invaluable habitat for other species including fish, mammals, waterfowl, songbirds, amphibians and insects.

Beavers have incredible foresight, ensuring their ponds have sufficient depth so as not to freeze to the bottom in winter so they can forage underwater for food all winter long. This depth also helps to regulate water temperatures during summer, which benefits other aquatic species, such as salmon, that could overheat in shallower waters.

They are also big on excavating. “They’ll dig canals going out from their pond so that when they forage for food, they can cut down a shrub and float it back to their lodge, rather than dragging it across the land. They prefer to float the food back because it’s easier, and they’re less vulnerable to predation. So they dig these canals, which are really important nursery areas for small fish,” Annette explains.

Hardly anyone makes that point about small canals and fish nurseries. Well done Annette.

Not only is the water table higher in the forests surrounding beaver activity, but the microclimate is more humid — which, in times of chronic drought, leads to healthier forests and ecosystems. Active beaver ponds also sequester an impressive amount of carbon. Each year, beaver wetlands (like our Columbia Wetlands) store about 470,000 tons of carbon globally.

Not only is the water table higher in the forests surrounding beaver activity, but the microclimate is more humid — which, in times of chronic drought, leads to healthier forests and ecosystems. Active beaver ponds also sequester an impressive amount of carbon. Each year, beaver wetlands (like our Columbia Wetlands) store about 470,000 tons of carbon globally.

Wow Annette, you are hitting all the points on our bookmark this summer. Nicely done.

Given how instrumental beavers are in protecting our landscapes — and our homes — it’s clear we should be doing our best to keep them around. North America’s beaver population has rebounded since protections were introduced in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, but it’s still estimated to be about 10% of what it was prior to colonization, and human activities continue to threaten beavers’ survival.

Given how instrumental beavers are in protecting our landscapes — and our homes — it’s clear we should be doing our best to keep them around. North America’s beaver population has rebounded since protections were introduced in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, but it’s still estimated to be about 10% of what it was prior to colonization, and human activities continue to threaten beavers’ survival.

One of the single biggest threats to beavers is trapping. ‘Problem’ beavers are regularly killed for impacting human infrastructure. When beavers’ handiwork floods a road or property, a permit will often be issued to dispose of the animal and destroy its habitat. If they compromise industry (by burrowing into the rail-bed within the wetlands or threatening a piece of road, for example) CP or the Ministry of Transport will hire a trapper to get rid of them.

Annette has tried to inquire as to how many permits are given out annually to kill beavers, but the government has refused to provide any information. Beavers are frequently trapped or killed illegally without permits as well, sometimes just to use the castoreum (castor sacks), or their meat as bait for hunting.

Hydroelectric dams pose another significant threat. Young beavers stay with their parents for about two years before venturing out to find habitat of their own, usually a few kilometres away. They’ll settle on what they think is a normal water body and try to establish a new lodge. But when water levels change quickly – from water being let out of a dam or building up inside it – the young beavers are wiped out.

Well I’m not that worried about hydro dams. Beavers are pretty darn good at floating. Even newborns. But this last section is straight from my heart!

How can we help beavers help us?

Practices can and should be in place to mitigate beaver conflict. Research has shown that relocation can be effective when done properly. There are also ‘beaver deceivers’ (aka pond levellers) which only allow beaver ponds to reach a certain depth, preventing flooding upstream. These contraptions trick beavers into thinking that no water is exiting their pond, simply because the flow is silent. They were developed based on an experiment done years ago to better understand where beaver’s instinctual desire to block water comes from. Scientists recorded the sound of running water on a cassette tape, played it on dry land near the stream overnight, and came back to find that the beavers had packed mud and sticks on top of it.

Practices can and should be in place to mitigate beaver conflict. Research has shown that relocation can be effective when done properly. There are also ‘beaver deceivers’ (aka pond levellers) which only allow beaver ponds to reach a certain depth, preventing flooding upstream. These contraptions trick beavers into thinking that no water is exiting their pond, simply because the flow is silent. They were developed based on an experiment done years ago to better understand where beaver’s instinctual desire to block water comes from. Scientists recorded the sound of running water on a cassette tape, played it on dry land near the stream overnight, and came back to find that the beavers had packed mud and sticks on top of it.

Much is left to be done to protect beavers and their ecosystems here in BC. “We’ve got all kinds of mountain bike trails and new roads and infrastructure that’s being built, and we have to figure out how we can adapt to that so beavers can come back,” Annette says.

As communities, we can anticipate locations where human-beaver conflicts may arise and pre-emptively install levellers that both meet beavers’ needs and mitigate flood risk.

If you happen to hear of a beaver conflict, inform people about positive alternatives to trapping or dam destruction. Suggest pond levellers or point them in the direction of helpful resources. Most importantly, share your knowledge: tell your friends and family how invaluable beavers are, and explain how they help preserve landscapes and homes. Now more than ever, it is time we stopped working against beavers — and started working with them.