How about a mystery to puzzle through this weekend? I heard about this a couple days ago and apparently it still hasn’t been unraveled. I have my primary suspect list involving the phrase “plausible deniability” of course, but the city denies involvement so I’m curious what you think.

Beaver Dam Destroyed In Shelton, Officials Investigating Why

SHELTON, CT — Shelton officials are asking for the public’s help determining why a beaver dam at Boehm Pond was destroyed.

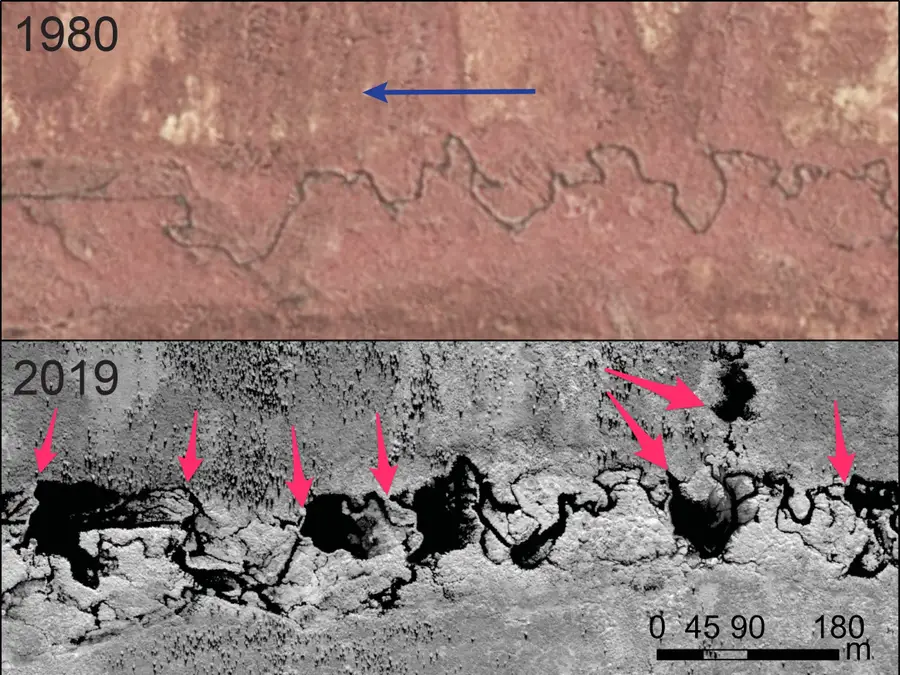

According to Teresa Gallagher, the city’s natural resource manager, the relatively new beaver dam was likely constructed around 2019 off Winthrop Woods Road and was a favorite sight for hikers in the area.

“Some people, especially hikers, loved seeing the pond and the dead trees, viewing it as a normal cycle of nature,” Gallagher said in an email to Patch. “It was a favorite spot for people to take pictures.”

In mid-December, Gallagher announced on the Shelton Trails Committee blog someone brought heavy equipment into the area and ripped the dam apart.

Well now I’ve surely known public works crews to do their really unpopular dirty work right before a holiday break so that no one will have to answer the phones until everything dies down. But maybe I’m hardened and too suspicious.

“Nevertheless, someone dismantled the guardrail on Winthrop Woods Road and brought in heavy equipment to rip apart the beaver dam, take out trees and move large rocks along the shore,” Gallagher said in the blog post. “People in the neighborhood assumed city crews had done the work, but no one at the city authorized or knows of any crews having done this.”

Will no one rid me of this meddlesome beaver? The misquote comes from Henry II who wanted someone to get rid of the archbishop of Canturbury Thomas Beckett without appearing to be directing folks get rid of Beckett. Four henchmen heard his cry and promptly dispatched the man of their “own” accord. Cities often function like little kingdoms. How many mayors have muttered under their breath for the problems to be “dealt with” so that someone could do in an unauthorized act what they themselves couldn’t be seen to do?

Will no one rid me of this meddlesome beaver? The misquote comes from Henry II who wanted someone to get rid of the archbishop of Canturbury Thomas Beckett without appearing to be directing folks get rid of Beckett. Four henchmen heard his cry and promptly dispatched the man of their “own” accord. Cities often function like little kingdoms. How many mayors have muttered under their breath for the problems to be “dealt with” so that someone could do in an unauthorized act what they themselves couldn’t be seen to do?

Gallagher said no further information about the beaver pond’s destruction has been received as of Thursday morning and the reason for it being torn up is still unknown.

“It was referred to the [city’s] Inland Wetlands Department since they have regulatory authority and can impose penalties,” Gallagher said.

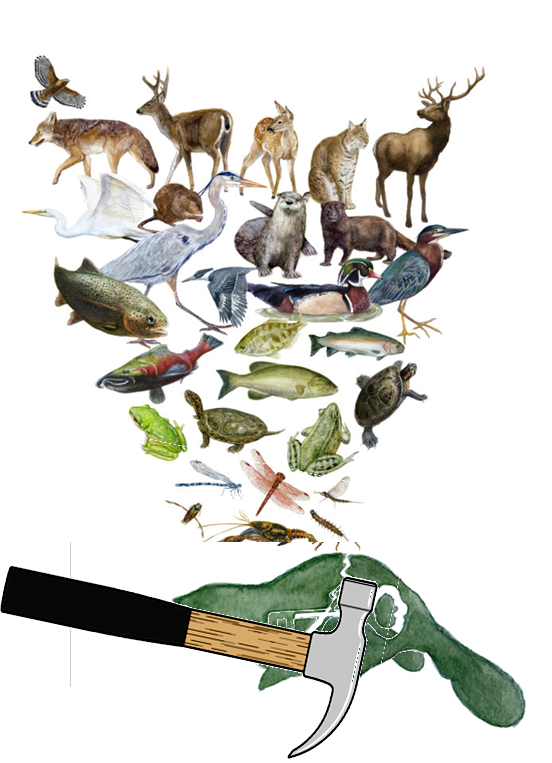

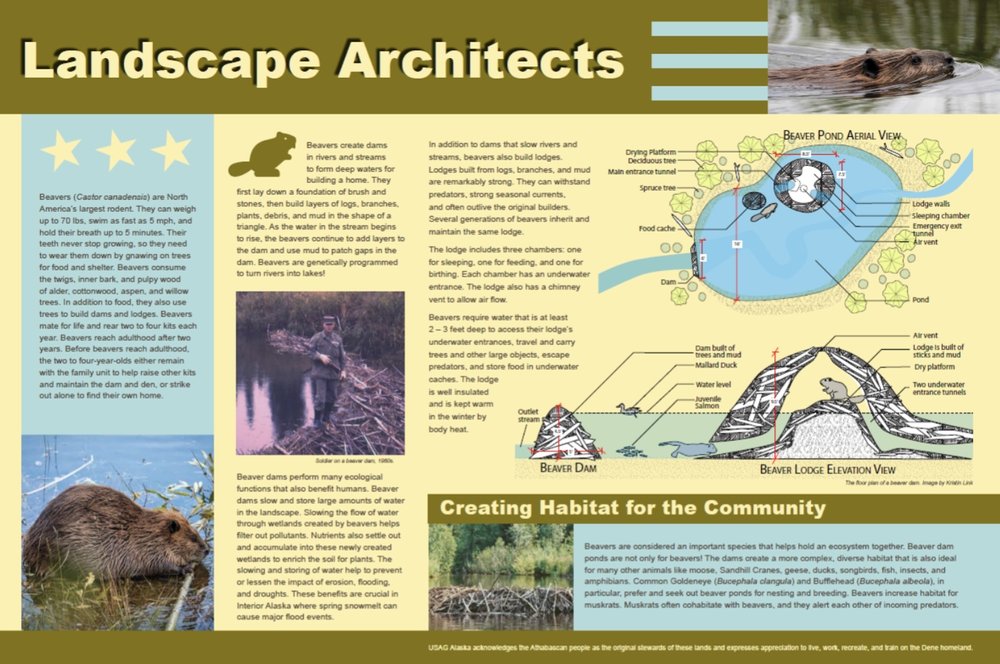

The larger shallow pond created by a beaver also benefits nearby wildlife, including fish, herons, ducks, turtles, frogs and otters. The dead trees are also used by breeding birds, including wood ducks and woodpeckers, and filled with insects as they rot that are eaten by woodpeckers and other wildlife, Gallagher said.

It’s such a shame someone would take all that away, The selectman’s just sick about it. Doesn’t this sound like some hardy buck passing to you?

Though hikers in the area and others have enjoyed viewing and taking pictures of the beaver pond and the wildlife it attracted, Gallagher noted some people in the neighborhood, conversely, thought the dead trees were an eyesore.

“It’s important to understand that the best wildlife habitat often looks messy,” Gallagher said. “Dead wood has high ecological value. Conservation lands are typically meant to be left untouched, and that means they will not look tidy or manicured. This summer, the dead trees will allow light to reach the ground and a rich layer of plants to grow, providing food and habitat for species such as deer and rabbits.”

The willingness to pass blame along to anonymous nosy neighbors is pretty much TEXTBOOK in my experience when it comes to mayor’s getting rig of problems without appearing to.

Case in point: A life time ago there was an incident when I expressed concern that with all the public attention at the dam a young teen was “fishing” right near the beaver kits and a kit actually darted toward his line in curiosity. I had visions of kits with hooks in their mouth or tangled in fishing line.

The mayor appeared to be concerned saying over the phone “That’s too bad, I fear the beavers may become victims of their own popularity” and to this day I’d swear I could hear him rubbing his hands together wistfully at the thought.

Anyone with information about what happened to the beaver dam is encouraged to email conservation@cityofshelton.org.

I’ve got a theory. Do you think I should email them?