I have been loving this National Parks Series on beavers. Today we get a new chapter from Bandalier National Park in New Mexico. I remember being amazed at the NM Beaver Summit when presenters talked about hiking down to reintroduce beavers with beavers strapped to their backs.

Under the Willows | Beavers Return To Bandelier National Monument

Under the Willows | Beavers Return To Bandelier National Monument

BANDELIER NATIONAL MONUMENT — Bandelier National Monument has had its share of natural disasters. In 2011 the Las Conchas fire burned 156,000 acres in northern New Mexico, much of it at Bandelier. And then, two years later, a devastating flood, the largest in recorded history, coursed down its narrow canyons. The landscape was drastically changed, from Ponderosa pine forests to rocky mesas and log-jam choked canyons. Nearly three quarters of the Frijoles Canyon’s upper watershed’s forest was destroyed.

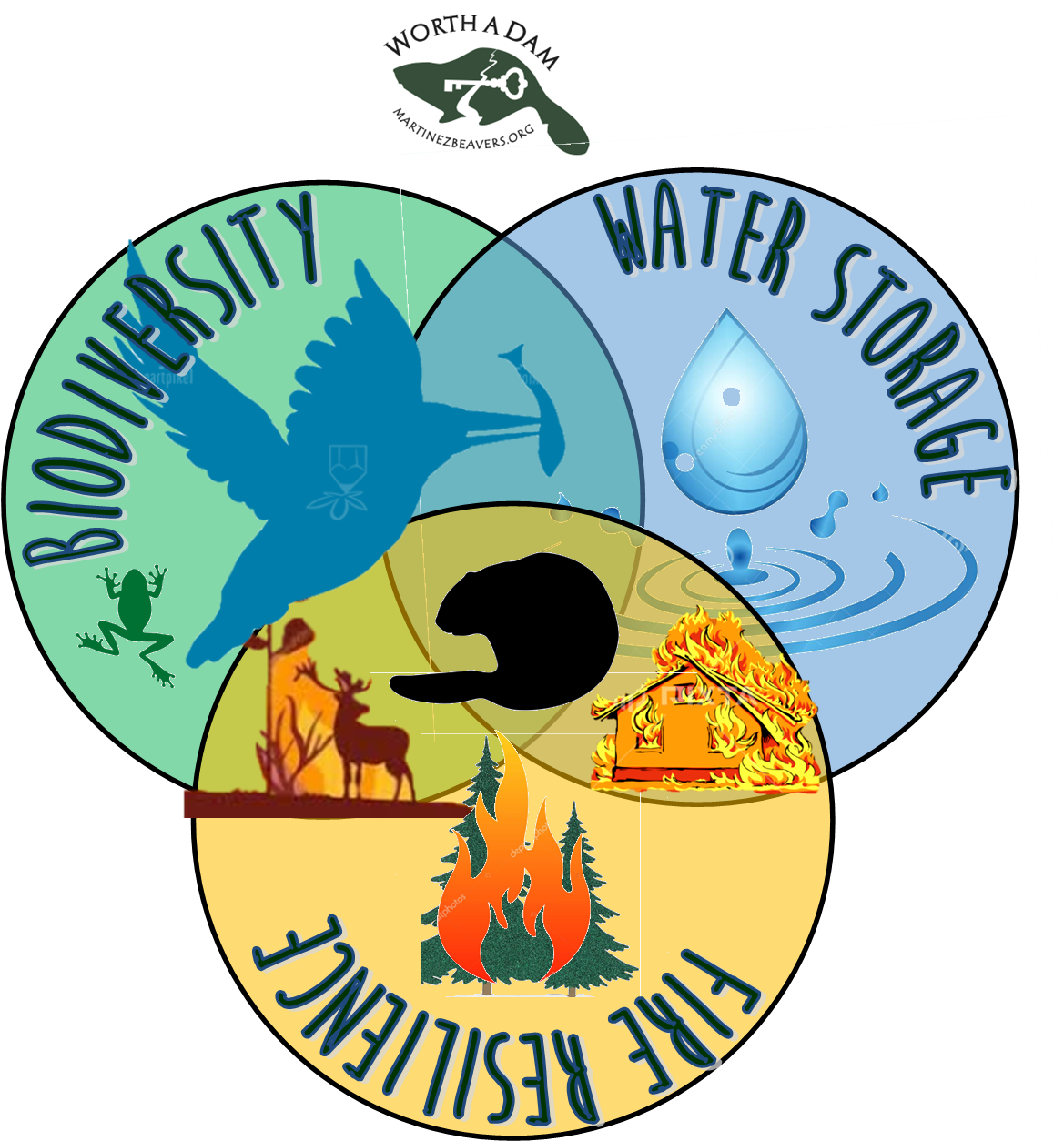

But when there is destruction, there is also rebirth and an opportunity for restoring the landscape, by recovering native fish species and the industrious beavers, known as a keystone species. They’re nature’s preeminent dam builders. Their keenly assembled piles of wood create ponds that support wildlife, aquatic species, and even act as natural firebreaks. They also slow stream flows, holding back precious water in this rugged desert landscape.

After decades of them being hunted and killed because they were flooding landscapes, cutting down trees and making travel in the narrow canyons difficult, beavers have made a comeback. In 2019 four beavers were introduced above the Upper Falls by the National Park Service. Since then, 27 beavers have been brought into the park and released. But the idea wasn’t a new one.

Isn’t that an excellent way to introduce the hero of the story? I sure wonder what California’s National Parks are doing about beavers. I really enjoyed this film and her bright explanations.

Ya gotta love an ranger that doesn’t want to drill a hole in a beavers tail and tells people not to walk on the dams! I have gotten such grief from all kinds of biologists and visitors for protecting ours in the day. “Oh don’t worry I do it all the time,” They’d explain. As if I were worried about THEM.

I’m sure if you’re Glynis Hood hiking in back country and never see a sole surrounded by beaver dams you might be able to get away with it. But in heavily trafficked areas, no. Just don’t. Resist the temptation to see if its strong enough to support you. It is. And it wasn’t build for you or because of you,

New Mexico Department of Game and Fish in 2018 to relocate problem beavers to prevent them from being euthanized,” she says. And, in a build-it-and-they-will-come scenario, the rangers constructed artificial habitats, called beaver dam analogs (BDAs), for them. They also planted native willows, an essential food source, which have thrived. And beavers are masters at managing willow stands, ensuring a stable supply.

New Mexico Department of Game and Fish in 2018 to relocate problem beavers to prevent them from being euthanized,” she says. And, in a build-it-and-they-will-come scenario, the rangers constructed artificial habitats, called beaver dam analogs (BDAs), for them. They also planted native willows, an essential food source, which have thrived. And beavers are masters at managing willow stands, ensuring a stable supply.

And Milligan recognizes that the beaver can create a place for other species to thrive.

“We are hoping they can establish themselves to provide habitat for our native but endangered New Mexico Meadow Jumping Mouse and native leopard frogs,” she said. “We also reintroduced native Rio Grande Cutthroat Trout in 2018 (and every year since) and they love using beaver ponds.”

Beavers are a heavy lift. Tell me about it! I feel like I’ve been carrying beavers on my back for fifteen years!

Their ponds have also been an ideal place to reintroduce native fish.

Their ponds have also been an ideal place to reintroduce native fish.

“The fires and floods that came through in 2011 and 2013 wiped out all of the fish, and we used that as a place to start from,” says Hare. “We only introduce native fish to the area. The first fish were introduced in 2018; the Rio Grande cutthroat trout. This year (2022) we brought Rio Grande chub and Rio Grande sucker, and used the beaver ponds to introduce them into.”

And as the beavers multiply, they’re starting to repopulate these canyons, supporting not just themselves, but every bird, fish, bear, deer, invertebrates and vegetation that rely upon them. In Bandelier (and many other parks) they’ve been transformed from a nuisance, to a solution.

Excellent closing solution. Of in city storm drains or urban ponds they were already a solution too, just not one for a problem people felt like fixing. I have a dream that one day there will be plenty of beavers in our wild spaces AND plenty of beavers in our urban in between spaces and everyone will realize what a fantastic solution they are and let the stay put.

Centuries ago, nearly every stream in today’s

Centuries ago, nearly every stream in today’s  To counter this, the National Park Service embarked on a program a dozen years ago to recreate habitat for beaver, protecting and nurturing willows by building a few dozen of these fenced areas – called exclosures, as they’re designed to keep ungulates out — covering more than 250 acres. And sure enough, by keeping ungulates from browsing on willows, the vegetation, and the indigenous beavers, have come back. “They don’t need a gigantic area of willows,” said Cooper. “Four acres of tall willow stands is enough to maintain a beaver population indefinitely.”

To counter this, the National Park Service embarked on a program a dozen years ago to recreate habitat for beaver, protecting and nurturing willows by building a few dozen of these fenced areas – called exclosures, as they’re designed to keep ungulates out — covering more than 250 acres. And sure enough, by keeping ungulates from browsing on willows, the vegetation, and the indigenous beavers, have come back. “They don’t need a gigantic area of willows,” said Cooper. “Four acres of tall willow stands is enough to maintain a beaver population indefinitely.” But beavers and their dams are not immune to natural forces. Forest fires can introduce mud and sediments into the streams, as happened two years ago during the East Troublesome and Cameron Peak fires, which scorched ten percent of the park. Flooding last spring along the Colorado River tore out dams, leaving broken twigs and logs scattered across the muddy sediments.

But beavers and their dams are not immune to natural forces. Forest fires can introduce mud and sediments into the streams, as happened two years ago during the East Troublesome and Cameron Peak fires, which scorched ten percent of the park. Flooding last spring along the Colorado River tore out dams, leaving broken twigs and logs scattered across the muddy sediments. And, as a changing climate intensifies the Western drought, rivers dry up, reservoirs shrink, and water managers are planning for the worst. But upstream in these mountains, along the Colorado River, a handful of organizations are planning for the future and taking action to restore a riparian landscape, and beavers are taking a starring role. The Kawuneeche Valley Ecosystem Restoration Collaborative is finding ways to work together with representatives from the National Park Service and U.S. Forest Service, Grand County, (Colorado), the Town of Grand Lake, The Nature Conservancy, the Colorado River Water Conservation District, and Northern Water, a nonprofit.

And, as a changing climate intensifies the Western drought, rivers dry up, reservoirs shrink, and water managers are planning for the worst. But upstream in these mountains, along the Colorado River, a handful of organizations are planning for the future and taking action to restore a riparian landscape, and beavers are taking a starring role. The Kawuneeche Valley Ecosystem Restoration Collaborative is finding ways to work together with representatives from the National Park Service and U.S. Forest Service, Grand County, (Colorado), the Town of Grand Lake, The Nature Conservancy, the Colorado River Water Conservation District, and Northern Water, a nonprofit.