They say a picture is worth 10,000 words, and that may be true. I would argue that aerial drone footage is worth a whole lot more than that. Emily’s shot of a beaver meadow in a burn scar outside Tahoe is more convincing than the mountain of positive words that follow it.

Yes, beavers can help stop wildfires. And more places in California are embracing them

A vast burn scar unfolds in drone footage of a landscape seared by massive wildfires north of Lake Tahoe. But amid the expanses of torched trees and gray soil, an unburnt island of lush green emerges.

But it wasn’t a team of firefighters or conservationists who performed this work. It was a crew of semiaquatic rodents whose wetland-building skills have seen them gain popularity as a natural way to mitigate wildfires.

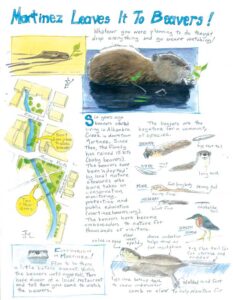

A movement is afoot to restore beavers to the state’s waterways, many of which have suffered from their absence.

“Beavers belong in California, and they should be part of our fire management plan,” said Emily Fairfax, assistant professor of geography at the University of Minnesota, who shot the drone footage of a series of beaver ponds along Little Last Chance Creek that remained green in the wake of the 2021 Beckwourth Complex fire.

This is a great article. A tour de force for the LA Times which has struggled to find out why beavers matter in the past. It even talks about the tools of coexistence and how CDFW has made funding available for landowners that can help with that.

It’s only missing two things as far as I can tell. First some kind of contact with some landowner that actually used those coexistence tools successfully for a decade and knows how they work.

But, honestly. where could they ever find someone like that?

And a discussion of the fact that AFTER fires beaver dams are going to slow down and filter the toxic runoff that ash and retardant flood thru the streams. Because after the fire can be more hazardous to more people in the long run.

I’ll give you one more money quote and then you can go read the rest of the article yourself. It’s weirdly not paywalled at the moment.

Karen Pope’s latest research, conducted in the Sierra and Plumas national forests, focuses on how people can rewet meadows in both burned and unburned areas by doing things like building beaver dam analogues. Preliminary results, which have not yet been published, are positive — after these structures were installed, some depleted meadows began storing groundwater pretty much immediately, she said.

The goals of these interventions are twofold: restore the wetlands, and entice beavers to move in and maintain them, Pope said.

“The ultimate endpoint is to have the beavers come back in and say, ‘We like what you did,’” she said.

Yup. That’s right. If you had 1000 acres of grazing land in the sierras wouldn’t you want there to be a patche of that green oasis in the middle of them?