I LOVE this man! What can we give him as a present for his retirement! A brass clock made out of a beaver chew? A golden compass pointing the direction of the nearest beaver dam? A fountain pen that was once owned by Enos Mills?

Whichever it is it’s gotta be something good. Because he’s a friend of ours. I can just feel it.

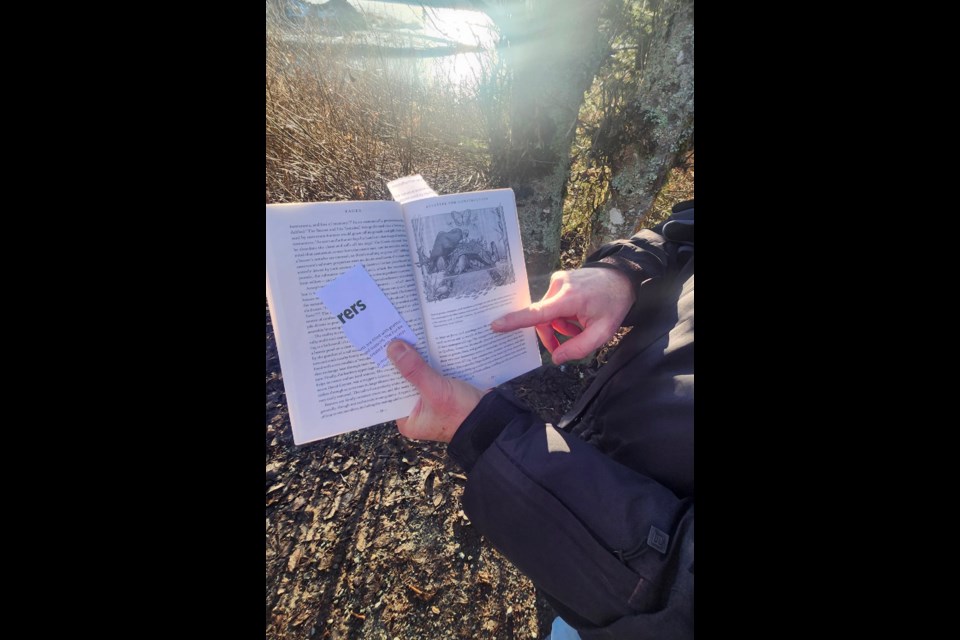

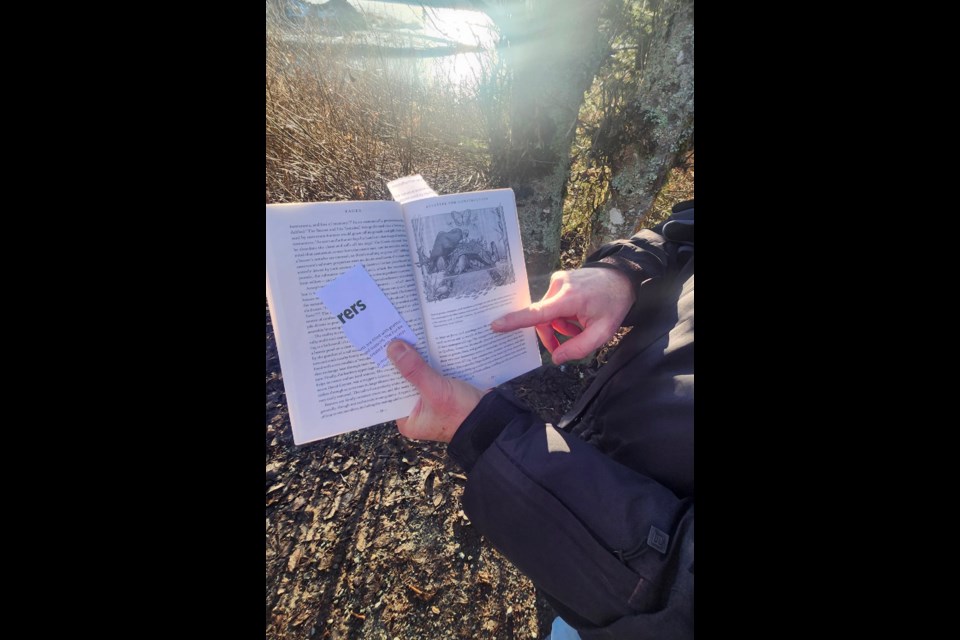

Ryszard Brykajlo has been engaged in a stalemate with Pemberton’s beaver population for the last six years. The trails around One Mile Lake are filled with evidence of his efforts to thwart the animals—stacks of sticks pulled from dams, cages around half-eaten trees and a massive rubber pipe that used to run beneath a dam.

Ryszard Brykajlo has been engaged in a stalemate with Pemberton’s beaver population for the last six years. The trails around One Mile Lake are filled with evidence of his efforts to thwart the animals—stacks of sticks pulled from dams, cages around half-eaten trees and a massive rubber pipe that used to run beneath a dam.

Brykajlo does it all out of a love for the beavers.

“I keep the beavers alive and they keep me in shape,” he joked. Now, closing in on his 75th birthday, he’s retiring as One Mile Lake’s “Beaver Man” and looking back on his battle with the toothy locals.

Pemberton is in BC Canada about 100 miles from our friends in Port Moody. But he’s clearly picking yp the vibes from Vancouver and the nearby believers. Good for him. I love this story. Can they show it every Christmas?

When he moved to Pemberton eight years ago, Brykajlo signed on with the Stewardship Pemberton Society (SPS) to help manage the salmon population—a volunteer role that involved counting fish and learning how to measure the health of critical creeks. During a count six years ago, he came across a strange feature: a dam on the outflow creek used by salmon during the annual migration to the ocean.

When he moved to Pemberton eight years ago, Brykajlo signed on with the Stewardship Pemberton Society (SPS) to help manage the salmon population—a volunteer role that involved counting fish and learning how to measure the health of critical creeks. During a count six years ago, he came across a strange feature: a dam on the outflow creek used by salmon during the annual migration to the ocean.

“So I contacted [SPS] and asked, ‘Why would someone build a dam here?'” recalled Brykajlo. “And a few days later, I got a reply: ‘That is definitely a beaver dam.’”

In addition to blocking salmon, damming the outflow creek could lead to stillwater on One Mile, creating the perfect breeding ground for bacteria that could render the popular swimming area unusable.

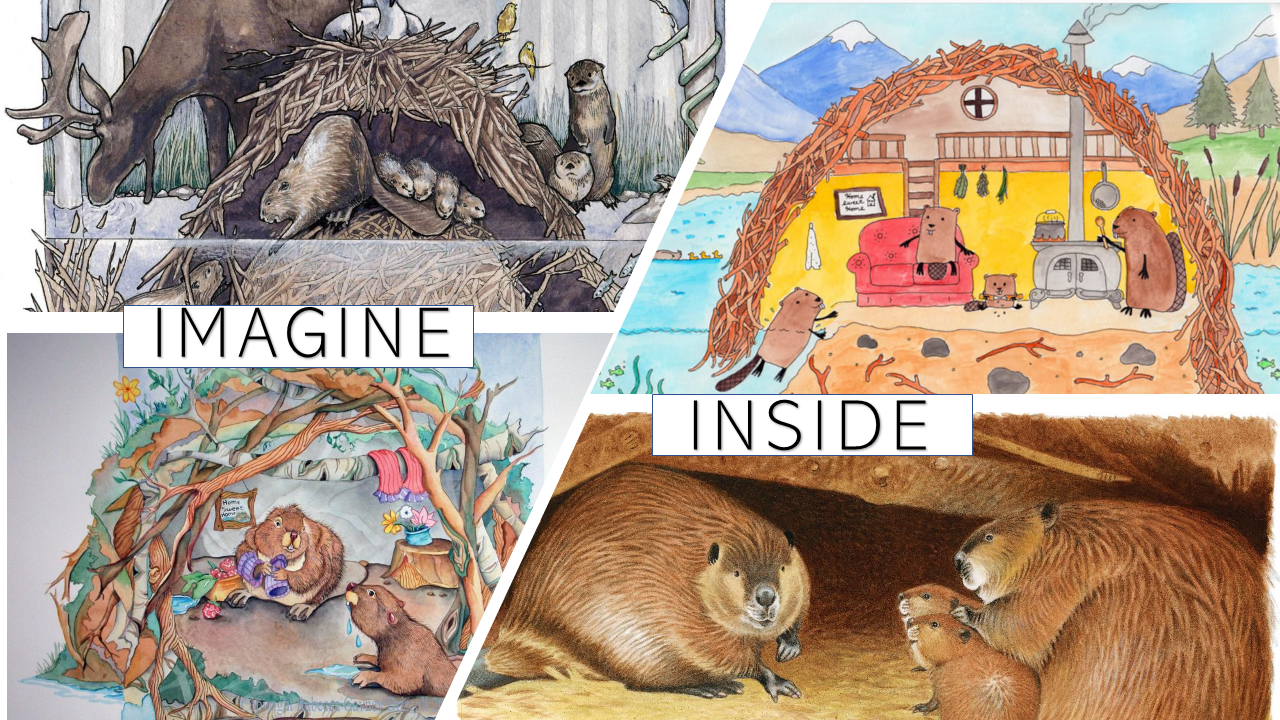

Still, Brykajlo was initially worried removing the dams would destroy where beavers live, but a subsequent review of the literature confirmed the animals don’t actually reside in dams. Beavers build dams in an effort to raise water levels, expanding their territory and offering protection from predators. They live in lodges, mounds of branches and other vegetation that sit on water at least five feet deep. Lodges typically feature two underwater entrances that help beavers escape from predators, a food pile, and an air vent. Lodges can usually house up to 12 beavers—though Brykajlo estimates One Mile only had two when he started his work.

The lodge at One Mile is visible and located near a dog-friendly beach at the northeastern end of the lake.

A man who does his research! Be still my heart! He’s a better investigative journalist than the New York Times!

That’s not to say that One Mile Lake is now devoid of beaver dams. Brykajlo recognizes the critical role beavers play in keeping ecosystems healthy, and allowed dams that didn’t impede salmon to remain.

That’s not to say that One Mile Lake is now devoid of beaver dams. Brykajlo recognizes the critical role beavers play in keeping ecosystems healthy, and allowed dams that didn’t impede salmon to remain.

“Especially when we have this uncertain weather, and we have these droughts,” said Brykajlo. “Beavers create these dams [which then] collect water.”

The inverse is true as well: beaver dams not only help prevent droughts, they can help minimize the impacts of floods. Dams help slow down the flow of water, which delays and reduces flood peaks further downstream.

Wetland habitats are bolstered by beaver dams retaining water, which in turn create spaces for other species, including fish, mammals, waterfowl, songbirds, amphibians and insects—strengthening an area’s biodiversity.

The same goes for plant diversity. Removing trees and flooding land allows for other plant species to emerge in their place.

“Because of how important the species are in the environment, there are all kinds of movements of people who call themselves ‘beaver believers,‘” Brykajlo told Pique.

“I’m a beaver believer.”

OH MY GOD. Do you think in pockets across North America their are mare park attendants like Ryszard ? We must meet them all. There could be a hall of fame.

SPS’ executive director Crystal Conroy said, although the society is working with the VOP on a beaver management plan, it isn’t actively looking for a replacement for Brykajlo right now.

“At Stewardship Pemberton, we will continue to advocate for ongoing maintenance of the dams in the channels to allow beavers to thrive in the area while helping to prevent vegetation overgrowth, keep the lake healthy for swimmers, and prioritize providing salmon access to return to their spawning location,” she said. “Working with the Village of Pemberton, we will continue to explore solutions that prioritize the well-being of the beavers and support sustainable management practices.

Brykajlo is optimistic about the beavers’ future. He hopes someone steps in to manage the animals to avoid a tough choice between having a growing beaver population or having healthy salmon runs and a swimmable lake.

The man must have a nephew in the area. Surely there’s some lad who enjoyed the park that is willing to work with the beaver Institute to fix this problem so it takes very little maintenance right?

“Maybe it is not very important, but this lake has a beaver,” he said. “Maybe there are some more important places for beavers. But I thought, ‘Where it is possible, every piece of work you do helps.’”

We are throwing him the BIGGEST retirement party with a beaver cake and a life time supply of bread sticks okay? This is a hero among men.

The Kahnawà:ke Environment Protection Office (KEPO) and the Public Safety Division of the Mohawk Council of Kahnawà:ke are pleased to update the community on the progress of a new beaver management program aimed at reducing human-beaver conflicts while preserving critical wetland habitats.

The Kahnawà:ke Environment Protection Office (KEPO) and the Public Safety Division of the Mohawk Council of Kahnawà:ke are pleased to update the community on the progress of a new beaver management program aimed at reducing human-beaver conflicts while preserving critical wetland habitats.