Yes, I am back and will only mention in passing my five unwilling days in the hospital with very exciting socio-political timing because hoades were picketing my hospital while I left. The units were scraped to bare bones and the nurses and techs were whispering together about grievances. And though I myself was an intern at kaiser once upon a time, have friends who work there now and know full well things are unbearable, and I generally support the rights of workers to collectively bargain, there are in fact, many, many more convenient times for said social justice than when I’m on the gurney.

But that’s all behind us. Let’s look to the future. In particular to the almost-but-not-quite-wonderful article in Bay Nature I never had the chance to write about since I was, as the say, indisposed right after it came out. If you’ll notice, it starts with Cheryl’s photo.

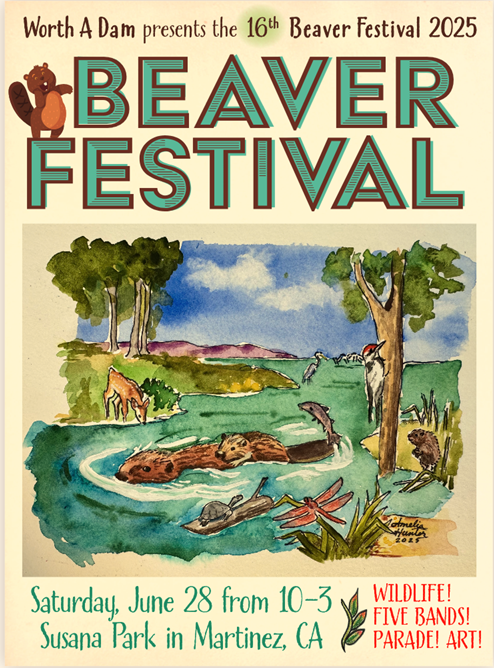

Early on in Eager: The Surprising, Secret Life of Beavers and Why They Matter, journalist Ben Goldfarb introduces us to a particular sect of animal enthusiasts-cum-environmentalists: Beaver Believers. “There is no single trait that unites Beaver Believers, besides, of course, the unshakable conviction that our salvation lies in a rodent,” he writes. They’re trained biologists and red state stockmen, “former hairdressers, physician’s assistants, chemists, and child psychologists.” But one thing Beaver Believers do seem to share is a certain unabashed fervor: an adherent we meet in Eager, Martinez resident Heidi Perryman, campaigns for the animal tirelessly on social media, maintains what Goldfarb describes as “the world’s largest collection of beaver-themed tchotchkes, knickknacks, and memorabilia” in her home, and founded and organizes the Martinez Beaver Festival every year. (At the 11th annual festival in June this year, Goldfarb himself appeared to promote the book.)

Ahem. Isn’t that nice? Now let’s see what they have to say about Ben and Beavers. Too bads she clearly didn’t actually read the chapter on Martinez, or the one on Logan Utah, or any of the ones that show case how beaver problems can be easily solved.

The wonders of biology aside, what really makes beavers miraculous is their ability to engineer landscapes. The animals can change their environments so fundamentally, in fact, that they’re practically a panacea for landscape ailments, as Goldfarb spends much of the book illustrating. Beavers dam rivers—a simple act that cascades outward thanks to the intricately interconnected nature of, well, nature. Damming rivers slows down their flow, which allows water to seep into the land. That, in turn, helps reduce floods, prevent erosion, and recharge aquifers (crucial for western states like California, where climate change threatens winter snowpacks that millions of people rely on for water). Beaver ponds serve as safe habitats for myriad other important or delicate creatures, from trumpeter swans to salmon of all kinds to the Saint Francis’ satyr, an endangered butterfly that exists only in North Carolina. And beaver dams help create wetlands, which filter out pollutants and collects nutrients from agricultural runoff that, if unchecked, causes dead zones in the ocean.

Ahhh nice. A specific link to California. So we know why they matter, just not how to tolerate them. Hmm, I thought the book made that pretty clear?

But the crux of the issue for me is: how complicated is it to change the way we feel about beavers? Is it a simple matter of engineering our way out of human-beaver conflicts, as Goldfarb suggests? Or does it involve deeper revision of our own society’s attitudes towards nature, to become able to cede control more gracefully, and accept sometimes significant tradeoffs for broader ecological benefit, as Goldfarb also suggests?

So when Goldfarb writes, in the book’s closing paragraphs, that “the only obstacle to returning to the Castorocene is that old hang-up, our cultural carrying capacity—forbearance toward an animal that defies our will,” it strikes me as oddly cavalier. Goldfarb’s own reporting shows us that even when all parties recognize the importance of beavers, actually getting them on the land and restoring ecosystems can be riddled with complications, as any ecological endeavor is. And “that old hang-up,” our limited tolerance for wild animals and the uncontrollability of nature, is rooted deep in the way we humans have historically understood ourselves and made sense of the world around us. I suspect it won’t be dislodged anytime soon.

And will that be because of the faults of the beavers. Chelsea Leu? Or because of the fault of the humans? We need powerful arguments spoken over and over again by compelling voices in the right place to the right people. And allow me to say frankly that your dainty review is helping no one.

Which is really too bad because I’d like to think Bay Nature knows better, and Ben’s awesome book is now on the longlist for the PEN Literary Science Writing!

By now, 6 months after its publication, I’ve heard Ben give a lot of interviews about his book, Eager: The surprising secret lives of beavers and why they matter. So many interviews, in fact, that while they still matter, nothing about a beaver’s life is secret OR surprising anymore. There is usually some part of the interview I wished he’d made clearer or some issue I wish he’d brought up. As somewhat of a connoiseur of the Ben-terview I have become his most adoring critic. But this interview with T

By now, 6 months after its publication, I’ve heard Ben give a lot of interviews about his book, Eager: The surprising secret lives of beavers and why they matter. So many interviews, in fact, that while they still matter, nothing about a beaver’s life is secret OR surprising anymore. There is usually some part of the interview I wished he’d made clearer or some issue I wish he’d brought up. As somewhat of a connoiseur of the Ben-terview I have become his most adoring critic. But this interview with T