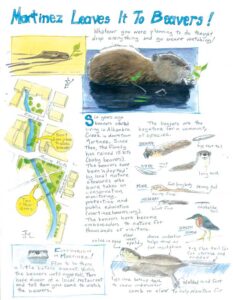

Once upon a time these stories were few and far between, and almost never from the likes of Calgary. I was happy to be reminded that times are changing.

‘We want to be able to live alongside of the beavers,’ says head of Elbow River Watershed Partnership  From the gravel on

From the gravel on

Mountain Road you can see the beaver’s work. There’s pools of water held back by stacks of twigs and branches. And headed into the thick of the woods, more of these animal-made dams.

It’s a pretty sight cast against the West Bragg Creek scenery.

The beavers really settled into the region after the 2013 flood. When these well-meaning engineers move in, they start working. Beavers are a bit compulsive: they hear flowing water, and have to block it up.

And while it’s great for wildlife and fish — fire, flood and drought resilience — it can be a bit of a headache.

“They created one dam which really threatened to flood our Mountain Road,” said Bragg Creek Trails crew lead Michele White.

“The beavers were really industrious. Their families were growing so they were creating more dams,” she said.

At this point, typically the beavers would be relocated, their dams destroyed. It’s a common practice for land owners who see them as pests, easy to remove and difficult to live with.

Well actually no. They would not normally be “relocated”. They would have been drowned. There is nothing in Calgary that allows legally for moving beavers. Why do people keep saying that there is?

But White said Bragg Creek Trails wanted to find another way.

But White said Bragg Creek Trails wanted to find another way.

Meetings between Alberta Parks, The Alberta Riparian Habitat Management Society, also known as “Cows and Fish”, and the Elbow River Watershed Partnership started. Together these experts had ideas about how to coexist with the beavers.

They settled on a pond-leveller: a pipe that’s installed upstream, shrouded with metal grate fencing, and wedged into the top of the dam.

“We want to be able to live alongside of the beavers, let them continue with their good work and then we can still enjoy the landscape from whatever perspective it is,” said the Elbow River Watershed Partnership’s executive director, Flora Giesbrecht.

“From this lens, it’s for recreation and then access for some of the infrastructure and especially in the winter, this road is very popular.”

Giesbrecht has seen some land owners embrace coexistence. Something she and all the groups helping today want to see more of.

Approvals for this kind of thing take time, several years in this case.

I’m so very glad that Cows and Fish is on the scene. They understand in a very deep way why beavers matter on the landscape and will direct you to the right tools for coexistence.

Grant money helped buy supplies, but the labour — that’s all volunteer work.

Grant money helped buy supplies, but the labour — that’s all volunteer work.

Riparian specialist Kerri O’Shaughnessy with Cows and Fish used the opportunity to teach the volunteers how it’s done.

As an added bonus, her crash-course will help get the Bragg Creek pond-leveller installed

“We’re doing it as a workshop and a learning opportunity for some interested like-minded organizations that are looking to do similar things in coexisting with beavers wherever they’re working,” she said.

They bend the fence into shape, cut sharp ends off, more bending. Once all the pieces are ready, the contraption is walked to the water, and waded into place.

“So once it’s in, if all goes well, we’re not going to see it at all, it’s gonna be underwater and it’ll be sort of like a permanent leak through the dam,” she said. “That is going to be good for beaver habitat, fish habitat as well as help mitigate the road issue.”

Hurray for long term solutions and hurray for Cows and Fish. I remember being impressed with them from the very start and they do not dissappoint

One last thing to get us in the mood for tomorrow;s women’s world cup. The country of Jon’s birth will be playing Spain and it will by all accounts be an astounding game. Spain is a dynamo, but when I watch the stately England Lioness back line dominate the ball I am reminded of the word “regal” so I was very delighted to see this:

A beaver has been named after England goalkeeper, Mary Earps, in honour of the team reaching the World Cup final.

A beaver has been named after England goalkeeper, Mary Earps, in honour of the team reaching the World Cup final.

Earps is the sixth kit born at the Paddocks enclosure at the Holnicote Estate near Exmoor.

The public voted for the name in a poll on The National Trust’s social media.

A ranger from the estate said: “We decided to continue with the sporting theme for the Paddocks family due to the success of the Women’s football team in reaching the World Cup final.”

The game is aired at 3 in the morning our time so I will be flashlighting it beneath the covers. Goooooo Team!

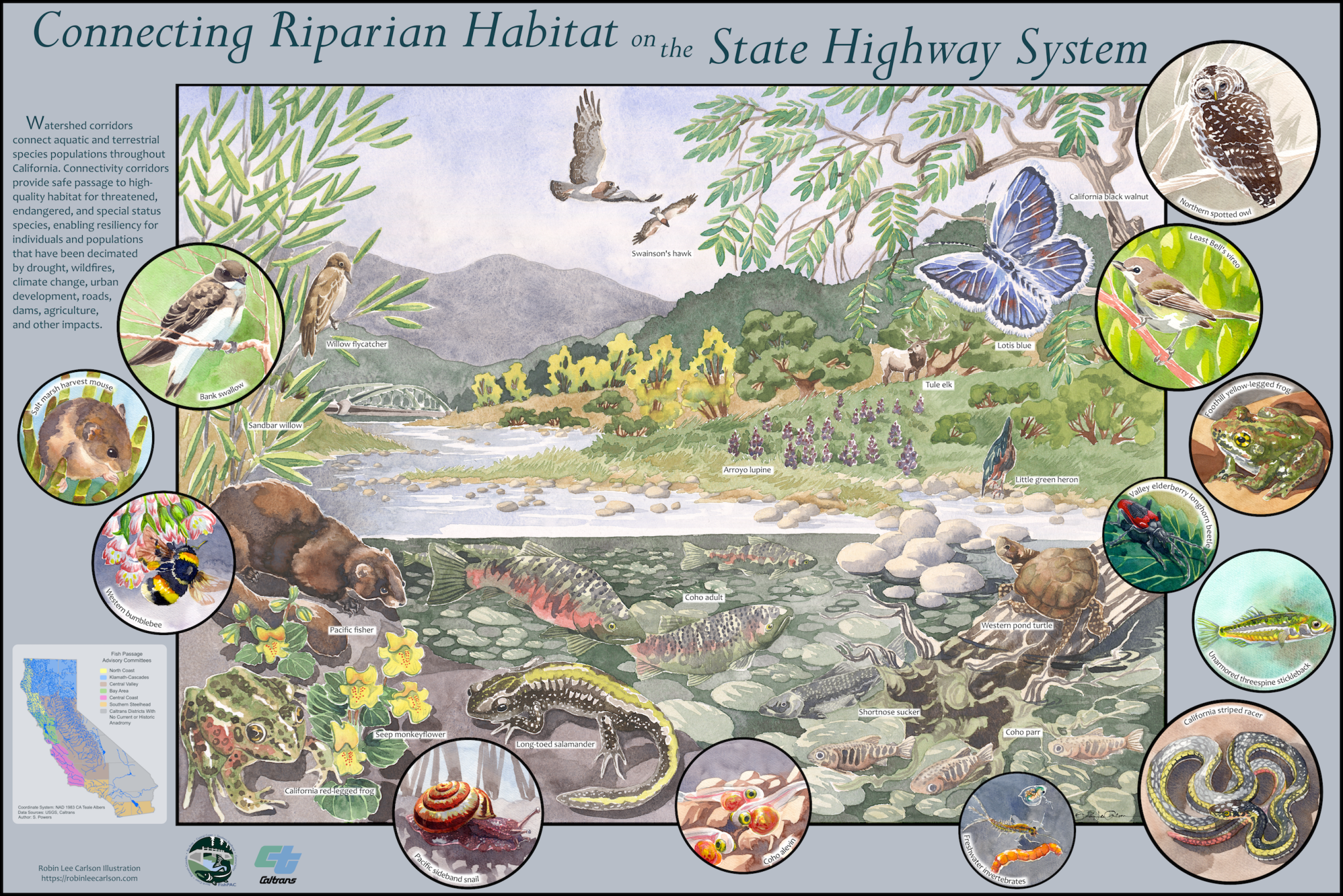

Robin is an amazing natural artist and author in California but from what I can snoop she hasn’t done many illustrations with beavers, She’s a buddy of Jack Laws though so I bet she’d be interested…. hmm…

Robin is an amazing natural artist and author in California but from what I can snoop she hasn’t done many illustrations with beavers, She’s a buddy of Jack Laws though so I bet she’d be interested…. hmm…

As Madison endures a long, hot summer of drought and wildfire haze, maybe it’s time to embrace what beavers have to offer.

As Madison endures a long, hot summer of drought and wildfire haze, maybe it’s time to embrace what beavers have to offer. But Midwestern attitudes may be changing and there are moves afoot to rethink beaver management. Boucher’s group,

But Midwestern attitudes may be changing and there are moves afoot to rethink beaver management. Boucher’s group,