Another fun video from our friend at Longfellow creek where she is watching closely how beavers and salmon cooperate.

Month: January 2024

Molly Foley is a beaver believer friend who crossed our path once a few years back and keeps in touch by way of the beaver management forum. She recently referred me to the beaver episode of the pod cast she enjoys called “Everything is alive”. The show basically uses a smart improv format to interview inanimate objects with the help of a shifting cast of comedians. ( Kind of like Dr. Katz professional therapist once did which will make me laugh hysterically until the end of my days,)

Molly Foley is a beaver believer friend who crossed our path once a few years back and keeps in touch by way of the beaver management forum. She recently referred me to the beaver episode of the pod cast she enjoys called “Everything is alive”. The show basically uses a smart improv format to interview inanimate objects with the help of a shifting cast of comedians. ( Kind of like Dr. Katz professional therapist once did which will make me laugh hysterically until the end of my days,)

All I can say is THANKS MOLLY!

Everything Is Alive is a podcast produced by Radiotopia and hosted by Ian Chillag. The show consists of bi-weekly fictional unscripted interviews with inanimate objects.

Well guess what they interviewed recently. Go ahead, guess.

And this delightful clip which didn’t fit in the episode and had to be cut.

Well Erica is interested in the origins of the Los Gatos beavers. I am not so wildly curious because that’s what beavers DO. They show up. They find their way through ditches and creeks and underground culverts. They just DO.

The Mystery of the Los Gatos Beavers

On the Los Gatos Creek Trail, right next to Highway 17, the sun dapples between willows and sycamores. I’ve reported on beavers for nearly a decade, including in my book Water Always Wins, yet I’m amazed to find them here, and not just because we’re surrounded by miles of suburban sprawl. I grew up in Los Gatos in the ’70s and ’80s, when it was still semirural: the high school had an agriculture program, our yard was sprayed with pesticide by helicopter to combat the Mediterranean fruit fly, and friends lived on unpaved streets and kept horses and chickens. Still, the only wildlife I remember were ducks and geese at Vasona Park and deer in the Santa Cruz mountains.

Yet other locals have seen beavers in the area from at least the 1990s, long before they famously returned to Martinez in 2006. Retired Santa Clara Valley Water employee Jeff Hopkins told me he remembers seeing the beavers’ handiwork in Lexington beginning around the early to mid-1990s. “I saw the beavers throughout my employment. We always went to see them and their tree cutting ability.” Jae Abel, a fisheries biologist with Valley Water, recalls seeing a beaver in a percolation pond downstream of Vasona Park in the early 1990s. My classmate Erica Cosgrove reports having photos of a dead beaver she saw in 2008 when the reservoir was drained for repairs.

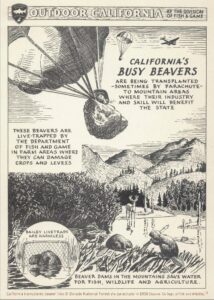

Exactly how the beavers got there is harder to pin down. One story has CDFW biologists relocating beavers from the Delta into Lexington reservoir just above Los Gatos in the mid- to late-’80s. Department employees recounted this tale a decade ago to Rick Lanman, the semi-retired doctor who has co-authored scientific papers documenting beavers’ history in the area. CDFW, however, wrote in a recent email that: “The Bay Delta Region staff has not found any documentation related to CDFW biologists relocating beavers from the Delta into Lexington reservoir in the mid- to late-‘80s. This remains unconfirmed.”

Okay but I’m CDFW has done plenty of things in its long life that went unconfirmed. And anyway are there river otters in Los Gatos? are you saying CDFW introduced them? Beavers just come to the party. Whether you incite them or not.

Abel heard a different story about the beavers’ origins—one passed along by two people who were directly involved. Abel prefaces his recollections by saying, “I consider this all secondary information . . . I didn’t write this down.” In the late ’90s an employee at Santa Clara County’s Vector Control District told Abel that beavers took up residence in the Alameda Flood Control Channel in the early ’80s. The employee was involved in removing them.

Infrastructure managers wanted the beavers gone but worried about public outcry. One of them asked a Valley Water board member where they could park some beavers. The board member knew a landowner near Elsman reservoir in rugged territory atop the Los Gatos Creek watershed, who agreed to accept the beavers into his reach of the creek. A few years later, Abel bumped into the guy. “We just started chatting. And he said, ‘Oh, yeah, that was me.’” According to the landowner, said Abel, “They didn’t stay on his property.” They settled in Lexington reservoir downstream, then continued to explore.

Now this sounds true enough because vector control is a fairly rogue district that usually does whatever it wants and gets away with it because mosquitoes are terrifying . I’m curious though whether the story Rick heard is wrong or whether neither or possibly BOTH are true.

The point is beavers are there now, And more are coming.

The Bay Nature beaver article is now available online if you want to check it out for yourself. It’s pretty good but it still needs better images if you ask me!

Believing in the Power of Beavers

Inspired by the science of beaver wetlands, activists tackle a long-held belief that beavers aren’t native to much of California.

Last winter’s parade of atmospheric river storms raised water levels in the Bay Area’s creeks, rivers, and reservoirs. Like most water utilities, Santa Clara Valley Water District, which serves the county’s two million people, releases water from its 10 reservoirs ahead of big storms to make space for new runoff. The risk of unplanned flooding was close in January, when creeks were overflowing and Uvas and Almaden Reservoirs were spilling. In response, Valley Water released big flows from its Santa Cruz Mountain reservoirs, and the water rushed down Los Gatos Creek and the Guadalupe River out into San Francisco Bay.

Last winter’s parade of atmospheric river storms raised water levels in the Bay Area’s creeks, rivers, and reservoirs. Like most water utilities, Santa Clara Valley Water District, which serves the county’s two million people, releases water from its 10 reservoirs ahead of big storms to make space for new runoff. The risk of unplanned flooding was close in January, when creeks were overflowing and Uvas and Almaden Reservoirs were spilling. In response, Valley Water released big flows from its Santa Cruz Mountain reservoirs, and the water rushed down Los Gatos Creek and the Guadalupe River out into San Francisco Bay.

In recent years, beavers and their handiwork have been spotted in several Bay Area counties: Santa Clara, San Mateo, Contra Costa, Napa, Solano, and Sonoma, and according to a good bit of evidence, they have quietly lived in the Santa Cruz Mountains since the 1990s. Meanwhile, California introduced new policies in 2022 that embrace beavers as partners in supporting biodiversity, healing water systems, and reducing fires. This appreciation, spurred by the work of activists and scientists, is a shift from earlier state policies over past decades that by turns allowed beavers to be hunted for fur or killed as nuisance animals, then protected them, relocated them, and enabled them to be hunted again. Today’s beaver-friendlier approach will catch up California with other western states.

They’ve even turned up on the pages of Bay Nature and you KNOW how hard that is to do. Beavers are blooming in the bay!

Activists Kate Lundquist and Brock Dolman, founders of the Bring Back the Beaver campaign of the Sonoma-based Occidental Arts & Ecology Center (OAEC), have played a significant role in stoking beaver support, according to the California Department of Fish and Wildlife. The environmental advocacy and education nonprofit OAEC’s online guidebook Beaver in California: Creating a Culture of Stewardship, most recently published in 2020, lays out the animal’s history. Prior to Europeans’ arrival in North America, the authors note, there may have been anywhere from 60 million to 400 million beavers on the continent. In much of California, they were as numerous as anywhere.

In recent years, the California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW) has not allowed beaver relocations, due to concerns about disease or competition, among other factors, says Erin Chappell, Bay Delta regional manager for CDFW. Instead, the CDFW has often issued depredation permits that provide permission to kill a beaver when people request them, for fear that the animals will cause flooding damage. Wildlife Services, a U.S. federal agency, reported lethally removing 541 beavers in California in 2022, using guns, neck snares, body-grip traps, and other methods. And more beavers are depredated by county departments.

County deparments? Is tgat some attenmpt to reference our depredation data over the years. It’s pretty simple really. CDFW hands out all the depredation permits. Even the ones to USDA which is federally run. USDA is legally obligated to track and report the number of species they kill. So this numbers are available to everyone. And about half of the beaver in California are NOT killed by USDA. And the only way any one even knows about that is because Worth A Dam has been reporting it for the past decade.

Activists have been pressing California to embrace coexistence instead. In addition to Lundquist and Dolman, others, including the California Indian Environmental Alliance, advocated for the funding of a new beaver restoration program. In 2006, when beavers moved into Alhambra Creek in Martinez and city managers wanted to remove them, Heidi Perryman founded the nonprofit Worth a Dam. Her work organizing a local annual beaver festival and the 2021 California Beaver Summit also brought Bay Area beavers to the public’s attention in the modern era.

In 2019 the national Center for Biological Diversity sued Wildlife Services, alleging that its beaver-killing also harmed endangered species. The result was a pause in depredation. Beavers are now considered ecosystem engineers because their activities create habitat for many other species.

There was not actually a pause in depredation. There was a pause in USDA DEPREDATION of SOME STREAMS tat=hat were listed already as important to salmon. Everywhere else was allowed to go right on killing beavers however they liked,

The threat to endangered species is real, Dolman says. In 2021, the minutes from community meetings in California’s Trinity River watershed area showed that a CDFW warden removed a beaver dam on private property against the landowner’s wishes, draining ponds. “The landowner and his family spent hours picking up all the dead coho, steelhead, giant salamanders,” Dolman recounts, “and took … these horrific gothic photos of hundreds of dead animals.” When asked about it, CDFW staff said the incident is under investigation and they offered no additional information.

Activists are working to tackle a long-held belief that beavers weren’t native to much of California. Dolman, Lundquist, Perryman, Rick Lanman, a semiretired doctor who has published journal articles about California wildlife, and others have amassed historical evidence on the presence of beavers in coastal California watersheds and in the Sierra Nevada. Three papers in CDFW’s quarterly journal California Fish and Game and a report for The Nature Conservancy, all published roughly a decade ago, cite extensive trapping records, beaver place names around the state, at least 20 Indigenous groups in California with words for beaver, and evidence of various groups’ use of beavers, as well as a beaver skull at the Smithsonian collected from Saratoga Creek in 1855; teeth and three bones found in the Emeryville Shellmound dating back approximately 700 to 2,600 radiocarbon years; and explorer accounts of beavers alive and dead.

Yes lets put Rick Lanman the senior author of the papers and the man without whom it could NEVER have been written last. Oh and Charles James, the BLM archeologist who had the presence of mind to carbon test the paleo dam in the first place? Lets not mention him at all.

Beavers can help bridge that storage deficit, according to research by Benjamin Dittbrenner, founder of Beavers Northwest, which facilitates détente between people and beavers. Tracking 71 beavers he relocated, Dittbrenner found that in rain-dominated basins, beaver ponds increased summer water availability by up to 20 percent.

Wetlands, including those created by beavers, are vital habitat for nearly half of threatened species in the United States. Humans have destroyed more than 90 percent of California’s wetlands.

Beaver water complexes can also act as fire refugia as well as firebreaks, according to ecohydrologist Emily Fairfax of the University of Minnesota, formerly of CSU Channel Islands. The benefits extend beyond the pond because plants can access the higher water table beavers create, making the plants less likely to burn. Evaporation from the ponds and plants’ exhalation of water, called transpiration, also feeds rain. Where beavers have been allowed to expand up and down a waterway, such as in the Methow Valley in Washington, they can create significant firebreaks, Fairfax has found.

You would think with all these amazing powers beavers would have shown jup in Bay Nature ages ago, wouldn’t you?

Unhoused people have also taken up residence along the banks of some waterways, including the Guadalupe River and Los Gatos Creek. With South Bay Clean Creeks Coalition director Steve Holmes, I walked down into the floodplain of the Guadalupe River near downtown San José. Trash was everywhere. Holmes sighed. “We’ve removed nearly 1.25 million pounds of trash,” he said, adding that he cleans the same areas again and again. “The whole thing is just really frustrating.” But his commitment to the animals keeps him going.

By June he had more encouraging news. San José mayor Matt Mahan was investing in short-term housing for people living in creek corridors. In April the federal Housing and Urban Development agency gave Santa Clara County $11 million to tackle homelessness, which joins Measure A, the nearly $1 billion bond measure that Santa Clara County voters approved in 2016 for affordable housing. And in June the EPA provided $3 million to clean up nine Santa Clara County waterways.

Despite the challenges, Holmes is inspired by beavers’ tenacity. “We have these salmon and beaver that have moved in and are making a pretty healthy living for the conditions that they’re facing,” he said. In response to my question on Los Gatos Creek about whether the beavers are still there, he pointed to trees with gnaws so fresh that bright wood chips still littered the rock below. “Absolutely.”

Just wait. We’ll co,e to your neighborhood soon enough. We swam into Bay Nature didn’t we?