Three times older than the pyramids and twice as old as Stonehenge, the statue was originally dug out of a peat bog by gold miners in the Ural Mountains in 1890. The remarkable seven-faced Idol was carved with a beaver jaw and is now on display in a glass sarcophagus in a museum in Yekaterinburg, Russia.

Beaver’s teeth ‘used to carve the oldest wooden statue in the world’

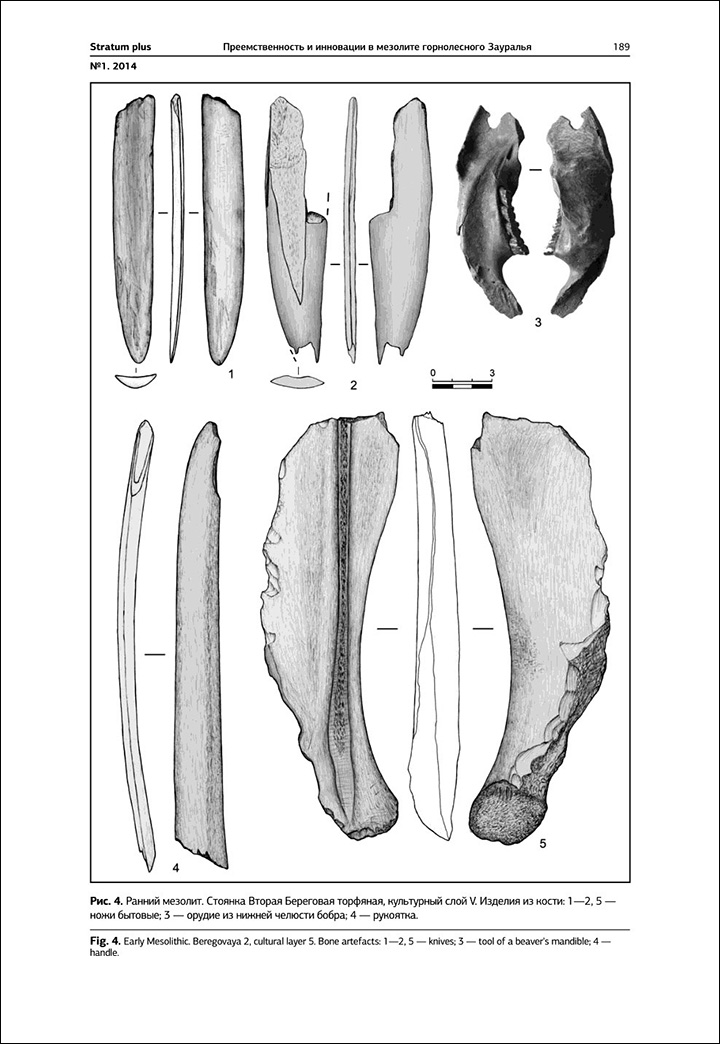

New scientific findings suggest that images and hieroglyphics on the wooden statue were carved with the jaw of a beaver, its teeth intact. Two years ago German scientists dated the Idolas being 11,000 years old.

At a conference involving international experts held in the city this week, Professor Mikhail Zhilin said the wooden statue, originally 5.3 metres tall, was made of larch, with the basement and head carved using silicon faceted tools. ‘The surface was polished with a fine-grained abrasive, after which the ornament was carved with a chisel,’ said the expert.

‘At least three [sets of teeth] were used, and they had different blade widths.

The faces were ‘the last to be carved because apart from chisels, some very interesting tools – made of halves of beaver lower jaws – were used’.

Zhilin, leading researcher of the Russian Academy of Sciences’ Institute of Archeology, has spoken previously of his ‘feeling of awe’ when studying the Idol, more than twice as old as the Stonehenge monuments in England.

‘Th is is a masterpiece, carrying gigantic emotional value and force,’ he said. ‘It is a unique sculpture, there is nothing else in the world like this. It is very alive, and very complicated at the same time.

is is a masterpiece, carrying gigantic emotional value and force,’ he said. ‘It is a unique sculpture, there is nothing else in the world like this. It is very alive, and very complicated at the same time.

‘The ornament is covered with nothing but encrypted information. People were passing on knowledge with the help of the Idol.’ Only one of the seven faces is three dimensional.

While the messages remain ‘an utter mystery to modern man’, it was clear that its creators ‘lived in total harmony with the world, had advanced intellectual development, and a complicated spiritual world’, he said.

The professor has found such a ‘tool’ made from beaver jaw at another archeological site – Beregovaya 2, dating to the same period.

Studying the Idol, he believed the tool is consistent with its markings, ‘for example when making holes more circular’, said Svetlana Panina, head of the archaeology department at Sverdlovsk Regional Local History Museum.

The idol was put on a stone basement, not dug in the ground, said Zhilin. It stood lik

e this for around 50 years before falling into a pond, and was later covered in turf. The peat preserved it as if in a time capsule.

I know I have very specific tastes in news, but that is sooo cool. Of course if there were ready made carving tools all around you would use them, rather than make your own. I’m assuming the fact that there were three sizes of tools means that they were three ages of beaver harvested?

Regular readers of this blog will know right away why it was the bottom mandible and not the top used for carving. I used to think this tusk-beaver from a bavarian crest was so silly -but it actually makes more sense than our modern bucktoothed cartoon.

Regular readers of this blog will know right away why it was the bottom mandible and not the top used for carving. I used to think this tusk-beaver from a bavarian crest was so silly -but it actually makes more sense than our modern bucktoothed cartoon.

Despite what the funny-papers tell us, lower teeth are much larger (which is why it’s so rare to get photos of the upper ones). One fine exception to that rule of castor is this wonderful photo taken by my facebook beaver buddy Sylvie Biber. That may not be her real name, considering, but I believe she’s eastern European, living in Scotland, where she took this wonderful photo.

You can bet I’d chose the bottom ones for my carving!

This also made me remember the research I did of the bay area tribes that lived near Brentwood and Antioch. In their burial grounds archeologists found beaver mandibles buried with the bodies and all their posessions. The paper I read said that no one knew why. Psychologist that I am, I always assumed it was because beaver teeth changed things and what do folks want to change more than death? But maybe they were precious tools, just being tucked away with the owner?