Month: February 2013

Recently there was another article about protecting trees by trapping beavers. I wrote the editor and received an invitation to write an op-ed in response. Okay then! I thought I’d practice here.

Trapping, as you know, is a short-term solution that will need to be repeated again and again when new beavers return to the area, often within the year. It almost always makes more sense to keep the beavers you have, solve any problems they are causing directly, and let them use their naturally territorial behaviors to keep others away.

Protecting trees is a fairly easy problem to fix. Wrapping them with in a cylinder of wire (not chicken wire because beavers are way bigger than chickens) 2×4 galvanized fencing is best and will guarantee the trees will be protected. Remember to leave enough space for the tree to grow! Another, less obtrusive idea is to use abrasive painting. Chose a latex paint that matches the color of the bark, and add heavy mason sand to the mix at the last moment, and paint the trunks to about 4 feet. The beavers dislike the gritty texture and will not chew. This will need to be repeated every two years or so.

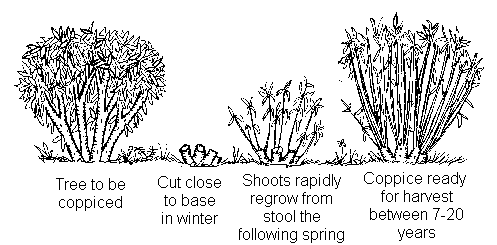

Remember that beaver chewed trees will ‘coppice’ which is an old forestry term referring to hard cutting back a tree so that it grows in bushy and more dense. This is why beavers are so important to the nesting numbers of migratory and songbirds – their chewing creates iprime real estate for a host of bird life. Willow is very fast-growing and if the stumps are left in the ground they will replenish quickly. In Martinez we have seen our urban willow re-flourish time and time again.

Research has shown that Beaver activity has a dynamic and generative impact on willow. In addition to cutting trees, their ponding and damming actually creates more ideal riparian border for willow to sprout. In fact some researchers have even referred to beaver as “willow farmers”. One USFS project in Oregon recently introduced beavers specifically to enrich the riparian border. Remember that in West Sacramento and Martinez beavers eat lots of other foods as well, including tules, fennel, blackberries and pond weed!

Research has shown that Beaver activity has a dynamic and generative impact on willow. In addition to cutting trees, their ponding and damming actually creates more ideal riparian border for willow to sprout. In fact some researchers have even referred to beaver as “willow farmers”. One USFS project in Oregon recently introduced beavers specifically to enrich the riparian border. Remember that in West Sacramento and Martinez beavers eat lots of other foods as well, including tules, fennel, blackberries and pond weed!

Why should a city learn to tolerate beavers? They are a keystone species that create a dramatic impact on the spaces they cultivate – even urban and suburban spaces. Here in Martinez we have documented several new species of birds and fish since they colonized our creek, as well as otter and mink! In addition, beavers are considered a ‘charismatic species’ which means that children love to learn about them and they provide a great educational tool for teaching about habitat, ecosystems and stewardship.

Why not involve the local boyscout troop or science class planting willow shoots every spring? To see these techniques first-hand for yourself, why not ride amtrak to Martinez and check out our urban beaver habit. We even have a beaver festival in August. This year will be the sixth.

Heidi Perrman, Ph.D. President & Founder Worth A Dam www.matinezbeavers.org So that tall guy in the middle is Mike Callahan of Beaver Solutions in Massachusetts. He came out for some fish passage seminars and went to check out some beaver habitat near Napa and then came to Martinez for a tour and dinner. It was one of those meetings that mean so much and still seem so familiar that afterwards you are saddened to remember that he doesn’t live across the street and won’t be coming back any time soon.

So that tall guy in the middle is Mike Callahan of Beaver Solutions in Massachusetts. He came out for some fish passage seminars and went to check out some beaver habitat near Napa and then came to Martinez for a tour and dinner. It was one of those meetings that mean so much and still seem so familiar that afterwards you are saddened to remember that he doesn’t live across the street and won’t be coming back any time soon.

I first wrote Mike in October of 2007. In case you didn’t realize that was a long, long time ago. Before Worth A Dam and before Obama and before our beaver mom died. Our contact armed me with information, made me hopeful and sometimes made me smile. It was often the thing that sustained and fortified me for the battle with the city, and gave me direction and a sense of purpose after we won.

Or, to put it another way; Mike recognized the sheetpile.

So it was entirely fitting to see him reviewing our beaver habitat. Have him scope out Skip’s installation. Spot the new lodge where our beavers are living and drive to our house for dinner. We of course handed over Alaskan Amber and a t-shirt so he would feel at home.

Lory and Cheryl and Jon enjoyed his visit and thought he was an easy-going, affable, force to be reckoned with. We swapped stories about beaver battles, massachusetts law, and flow devices. He had met Sherri and Ted Guzzi of the Sierra wildlife coalition the night before and had made good contacts at the conference.

Lory and Cheryl and Jon enjoyed his visit and thought he was an easy-going, affable, force to be reckoned with. We swapped stories about beaver battles, massachusetts law, and flow devices. He had met Sherri and Ted Guzzi of the Sierra wildlife coalition the night before and had made good contacts at the conference.

He talked a little about his ideas for adapting flow devices to make fish passage in very low flow easier. We discussed one way gates and counters that will track the number of fish that use them. The social science side of my brain forced me to suggest that his study should include a control group so that the fish that make it over a flow device with no modifications could be counted too, and he thought that was a good idea.

And now, sitting on this side of the meeting, I notice I am wistful, and feeling like I came to the end of some chapter in my life. Mike was the first glimmer of support that I looked to for our beavers, though he certainly wasn’t the last. The story of the Martinez beavers and the teaching role they had on other communities will continue in ways I can’t even imagine today, but this part of the story is completed. The circle that I never dreamed of starting, that caused me to work harder than I ever had and do things I never had never attempted before, that took me places I could never even dream, that part of the circle has been closed.

And now, sitting on this side of the meeting, I notice I am wistful, and feeling like I came to the end of some chapter in my life. Mike was the first glimmer of support that I looked to for our beavers, though he certainly wasn’t the last. The story of the Martinez beavers and the teaching role they had on other communities will continue in ways I can’t even imagine today, but this part of the story is completed. The circle that I never dreamed of starting, that caused me to work harder than I ever had and do things I never had never attempted before, that took me places I could never even dream, that part of the circle has been closed.

Trophic level refers to an organism’s position on the food chain. It’s from the greek word τροφή meaning food. One popular strain of ecological thought follows trophic levels down the chain to study their impact: as in wolves eat elk. Elk eat willow. More wolves mean fewer elk and more willow, right? End of story.

Trophic level refers to an organism’s position on the food chain. It’s from the greek word τροφή meaning food. One popular strain of ecological thought follows trophic levels down the chain to study their impact: as in wolves eat elk. Elk eat willow. More wolves mean fewer elk and more willow, right? End of story.

Maybe not.

This kind of thinking leaves awesome gaps so wide that you could sail a scholarship through. For example, certain flat-tailed animals, (I won’t give the answer away) trigger a feed back loop that changes the top-down interaction. For example, wolves eat elk, fewer elk mean more willow, more willow means you can have more beaver, and beaver in addition to eating willow, create conditions that inspire more willow to grow!

Food chain of command changed from both ends! Enter Kristin Marshall Ph.D. Ecology Colorado University.

Trophic cascades in action

This is a classic example of a popular theory in community and food web ecology– trophic cascades. The story goes like this: top predators (in this case, wolves) prey upon herbivores (elk) and control their population size. Herbivores feed on plants, and when herbivores are controlled by predation, plants do better. If top predators are removed, herbivore populations increase, more plants are consumed, and overall plants do worse.

Back to our story. In 1995, something really miraculous happened in Yellowstone. There was enough interest and political will to allow Park biologists to reintroduce a few wolves, and then a few more the following year (you can find more backstory in this book). Wolves quickly became established on the northern range, and their population grew. They preyed upon the large elk herd, and elk numbers declined (other factors contributed, like people hunting elk outside the park boundaries).

Declining elk numbers should mean that plants should do better, right? That’s what the ecological theory predicts. But it turns out the story is a bit more complicated.

Beaver dams have key feedbacks to willow stands. They raise water levels behind the dam, giving willow roots easier access to water, and increase flooding, a disturbance required for willow reproduction.

Who was it that said “beavers change things; that’s what they do“. Oh, right that was ME. I’m delighted that your missing link turned out to be castor in nature! Kristin when you’re done researching Yellowstone, maybe you’d appreciate a trip to Martinez? We would be happy to help you get to the bottom of this…

Have you noticed that something cultural gets a little unhinged in the winter months? When the ‘snow’ hits the ground folks turn all ‘man-against-the-wildernessy’ and we get cheerful articles about trapping coyotes or fishers and why otters are worth hunting.

Have you noticed that something cultural gets a little unhinged in the winter months? When the ‘snow’ hits the ground folks turn all ‘man-against-the-wildernessy’ and we get cheerful articles about trapping coyotes or fishers and why otters are worth hunting.

Case in point:

The day I nailed a frozen beaver carcass to a tree

I’m willing to try anything once, but I never thought I’d hammer a frozen, skinned beaver to a tree.

But that’s what I did last week when photographer Leah Hennel and I joined Mirjam Barrueto, a research associate with Wolverine Watch, for a day in the field to learn more about the survey.

Mirjam did the heavy lifting. Literally. She hauled the 10- to 15-kilogram beaver carcass (I’d say it was closer to 15 kilograms) and broke the 600-meter snowshoe trail in knee- to thigh-deep snow to the Bow River site, which is easier than some of the backcountry sites they visit.

Sometimes I read beaver-killing articles and I worry if I’ve grown too rarefied and overly sensitive. Maybe I don’t understand the larger geo-political context of trapping beavers. Maybe I’ve become too “beaver-centric”, with unreasonable alliance to the animal I’m representing.

And then I read an article like this beaver crucifixion and think: “Are you frickin’ kidding me???”

Yes wolverines are cool and studying them is cool and the beaver was already dead and skinned anyway and that’s a fairly purposeful end to his pointlessly de-purposed life BUT I have to ask, what if wolverine’s favorite food was house cats, or lapdogs or babies. Would you still post a photo of yourself nailing one to a tree?

If you want to see the gristly diorama for yourself you’ll have to go to the site. At least I got the writer interested in going on a real beaver trek one day….